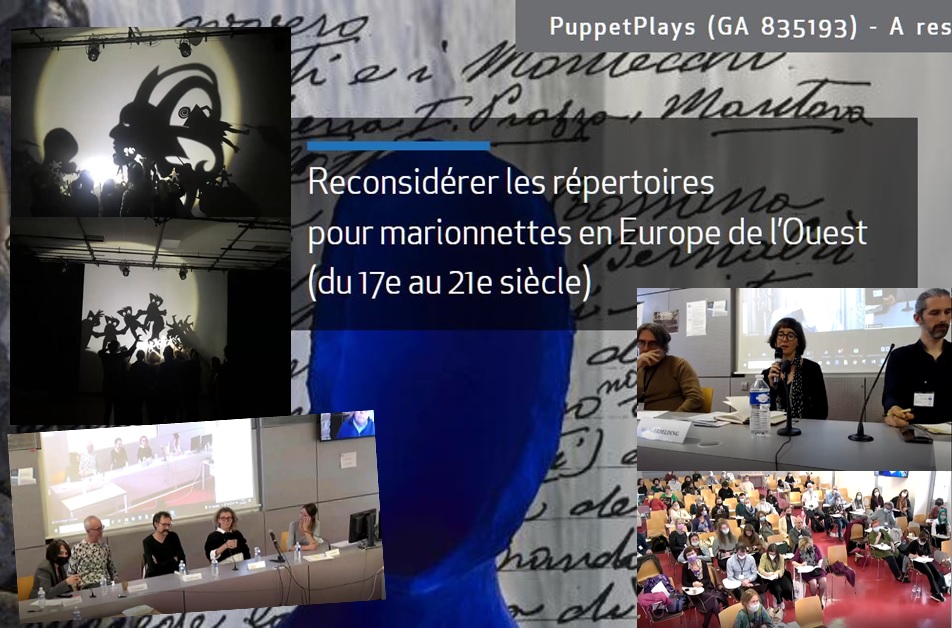

With this article we bring to an end our account of the PuppetPlays International Conference on Literary Writing for Puppets and Marionettes in Western Europe (17th to 21st centuries). The Conference was held in France at the Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, the organising institution, from Thursday 14 to Saturday 16 October 2021.

Having focused on the lectures delivered during the Conference in PART I and PART II, we deal here with the Keynote speeches that introduced the programme of the day: on Friday 15 October it was the writer Joseph Danan who spoke and, on Saturday 16 October, stage director Bérangère Vantusso opened the events. We then turn to the Workshop given by the company from Lisbon, A Tarumba, together with Paulo Duarte. An overview of the meetings between authors and critics, which closed the Conference, brings this account to an end.

How (and why) have I (still) not written for puppets?, by Joseph Danan

Joseph Danan, Professor in Theatre Studies and well-known French playwright, posed this rhetorical question in order to talk about what it would mean for him to write specifically for puppets. He commented that he had never actually felt the need to create plays for puppets, while confessing that, either directly or indirectly, he had indeed written works that were suitable for puppet theatre.

Highly ironic and opening his talk with succulent word play and paradoxes, Joseph Danan gradually introduced what could be considered his dramaturgical point of view on how to deal with the puppet in contemporary dramatic writing. Furthermore, he did so with the keen eye of someone who is capable of being both inside and outside the writing process, looking at various texts by writers who are open to worlds where the puppet seems to be either a necessity, indispensable or, at least, plausible. First, the play À la carabine by Pauline Peyrade, and then Les gens légers by Jean Cagnard, commissioned by the company, Arketal.

Image of ‘Les gens légers’ by Jean Cagnard, Arketal company

Image of ‘Les gens légers’ by Jean Cagnard, Arketal company

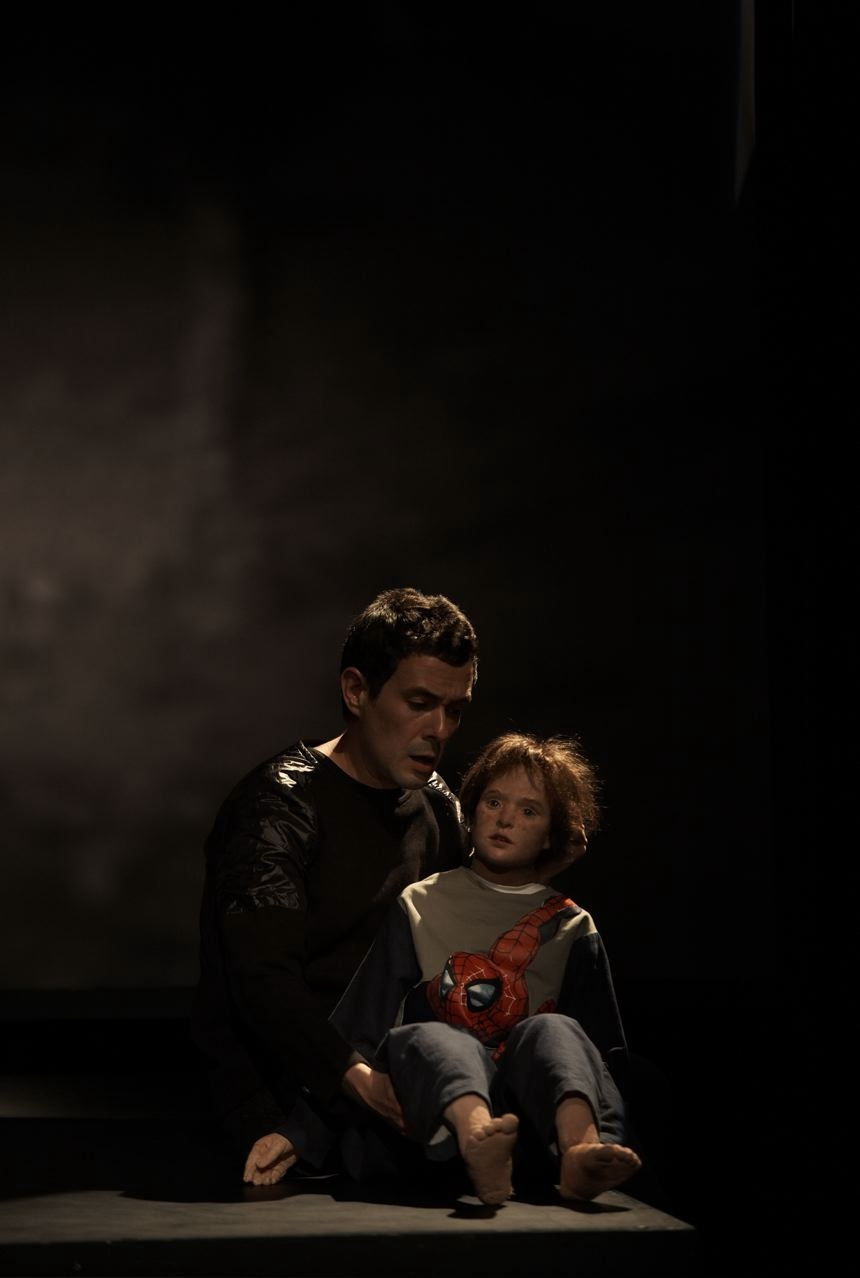

He also spoke about two of his own works that, in retrospect, he realised contain the puppet. Specifically Sur la terre moins qu’au ciel is, in all senses, a play written to be performed with puppets; the characters are a baby, its parents and its grandparents, the peculiarity being that the latter are dead. The dialogue between the dead couple is situated: ‘Outside (Ailleurs), either in the same place or in a placeless place’; according to the stage directions that introduce this dialogue.

Joseph Danan’s other text in which the puppet ‘slips in’ is Le Théâtre des papas, in which a father constructs a puppet theatre for his son and, among other things, performs the entire history of Humanity.

We will not try to summarise the scalpel-fine theory with which Joseph Danan analysed these and other plays, so as not to betray the wealth of subtle details that merit close attention (you can listen to his talk here) but I will outline a number of notable points that strike me as particularly significant:

Joseph Danan during his talk

Joseph Danan during his talk

– the observation that nowadays, ‘contemporary playwrights do not necessarily imagine a scene, at least not at the time of writing. They do not consider the performance as something that will naturally follow the writing process, but as a question, a question mark. It is here that the puppet and the object appear, in this abandoning of naturalism; not as the more or less codified reproduction of types and archetypes, as was the case in the past, but as a stimulus for the imagination.’

– speaking about an unpublished work of his, Si j’étais un homme, whose central character is a robot, Joseph Danan says: ‘What interests me here is how theatre can bring the human being face to face with something different: animal, object, robot, machine…, as a way to interrogate, perhaps, the limits of the human.’ He underlined that what interests him in this confrontation corresponds to Hélène Beauchamp’s formulation of this idea in an article in the magazine, Europe: ‘the manner of making something exist, of establishing a relationship – both on stage and in writing – between man and the others that are not him, others to whom normal life and the traditional stage do not give any status but that of object. It is not only a question of animating or giving life to things, materials, puppets, but rather illuminating an extraordinary network of relationships between the human and non-human.’

– or when, after remarking on Les gens légers by Jean Cagnard, a play that talks about the Shoa but without mentioning it, using only images that reflect it very indirectly in a work that begins and almost ends with a train journey, a normal journey, Joseph Danan says that here ‘the puppet assumes its role fully, by allowing us to look the indefensible in the face, to present the unpresentable, giving the puppet access to an aesthetic dimension that makes us think that, rather than allowing itself to be swallowed up by pathos, it authorises a form of catharsis. Because it is necessary to live, but to live without forgetting.’

These fine-tuned observations give us an insight into some of the most interesting currents in contemporary writing for puppetry.

The theatrical concerns of Bérangère Vantusso

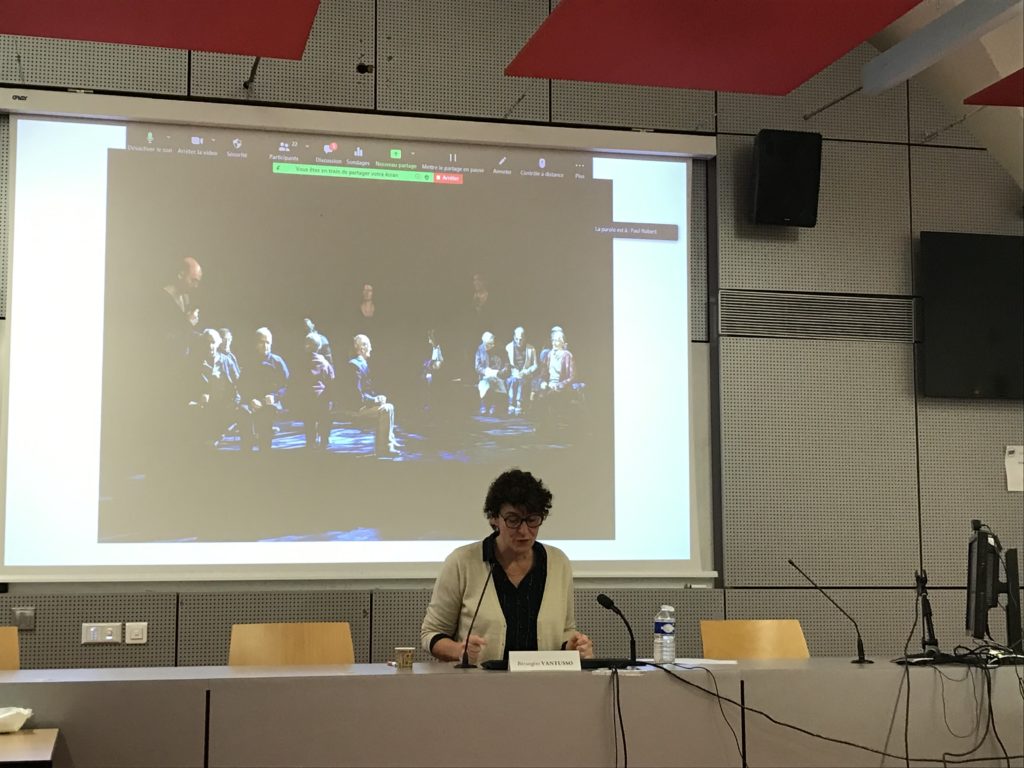

The Keynote speech introducing the Saturday session on 16th October, the last day of the Conference, was given by stage director, actor and puppeteer Bérangère Vantusso. Artistic director of the company Trois-6ix-Trente and Studio-Théâtre, centre for theatrical experimentation in Vitry-sur-Seine, her talk was titled ‘The chicken and the egg – texts at the heart of the company Trois-6ix-trente’.

Bérangère Vantusso during her lecture

As Didier Plassard stated, introducing Bérangère Vantusso, it was indispensable that this meeting between literature and puppetry should include artists, and not only academic and university-based points of view, in order to bring together practice with theory and reflection.

Inviting this versatile and multifaceted woman of the theatre was a brilliant idea. She trained as an actor, and became involved in puppetry in 1998, through François Lazaro, Emilie Valantin, Michel Laubu and Sylvie Baillon. She was lucky enough, too, to take part in the meetings between authors and theatre makers organised by La Chartreuse (National Playwriting Centre) in Villeneuve lez Avignon. In 1999, she created the company Trois-Six-Trente (three people, six hands, thirty fingers), with a focus on experimental theatre where ‘puppets, actors and sound composition can be found, at the service of contemporary writing’.

Image of ‘Alors Carcasse’. Photo by Ivan Boccara

Specifically, the play she directed Alors Carcasse by Mariette Navarro, was the production offered as part of the Conference, with nightly shows at the Théâtre la Vignette, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3.

Bérangère Vantusso’s decision to concentrate on hyperrealistic puppets thrust the company into the spotlight. This line of work, which in the end lasted for ten years, began with a production of the play Kant by Norwegian author Jon Fosse, since they needed to create a puppet for the child protagonist that appeared to be a real child. She centred her talk in Montpellier on four of her productions:

– Les Aveugles, by Maeterlinck (2008)

– L’Institut Benjamenta, from a text by Robert Walser (2016)

– Alors Carcasse, by Mariette Navarro (2020), and

– Comprendre la vie, by Charles Pennequin (2020), which she mounted with young students from a School of Dramatic Arts in Montpellier. A multifaceted text, combining story-telling, recitation, poetry, song and more.

The first two shows belong to the period of hyperrealistic puppets, while, in the third, Bérangère Vantusso engaged with the puppet at the simplest level of expression of a piece of wood.

Vantusso is interested in themes such as marginalisation, domination, opposition, and the rebellion against a system that attempts to impose a rigid way of seeing the world, whether social, ideological or religious. However, the common thread in her productions is perhaps, above all, the notion of emancipation, which allows the relationship between puppet and puppeteer to be expressed through the play of opposites and to evolve over the course of the work.

Image of ‘L’Institut Benjamenta’, by Robert Walser. Photo, company Trois-6ix-Trente

The aesthetic of puppetry has also influenced her texts, as was the case throughout the cycle with hyperrealistic figures. On other occasions, it is the text that defines and conditions stage aesthetics, as happened in Alors Carcasse, a play where, at first, the company had no idea in which direction the text would lead them.

The way Vantusso defined the organising principles of her work was very interesting, synthesising them into four groups of key words:

– duality, sometimes an otherness or a polarity, that generally leads to transformation, to change. The relation actor/puppet is not stable, it is constantly modified, and it tends to mark the dramaturgical mechanisms of the play. This is a central duality in her work because, more than the puppet itself, what interests her is the relationship between the actor and the figure, how to develop it in its multiple possibilities. These relationships determine the scale and dimensions of the puppet, as well as the number of actors needed for each one.

– the presence of the body considered as object, or made into a metaphor, something very evident in Alors Carcasse, where the body is constantly objectified.

Image from ‘Kant’, by Jon Fosse. Photo, company Trois-6ix-Trente

– the theatre seen as a laboratory or an observatory of human life. Community is preferred over the individual, characters are not usually named, being more generic. This aspect is often reinforced by the text, with stories in which the third person has greater weight than the first person.

– the irruption of the fantastical at the heart of the text, never treated as arising from any kind of dream but involving subtlety, invisible presences, the invisible, and so on. In Les Aveugles, for example, nature becomes increasingly invasive, the characters can feel the stars, they pick up presences around them.

Bérangère Vantusso said: ‘I realise that, when all is said and done, the guiding thread that most interests me is that of the puppeteer more than the puppet, or rather, it is the relation between the two. I avoid realism and psychology; I side with the actors and mistrust beliefs in general. I like to think that the scene takes place in the minds of the audience. I love poems and theatrical conventions, and the puppet is an ideal guide to new theatrical forms.’

Laboratory workshop on experimental dramaturgy, run by A Tarumba and Paulo Duarte

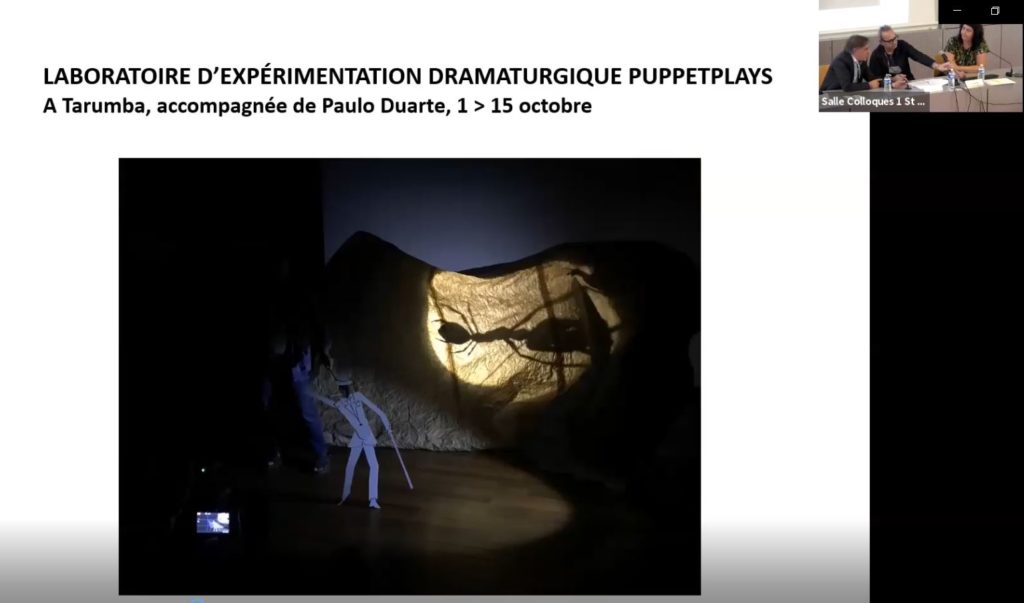

One of the most interesting and impressive activities held as part of the Conference was the laboratory workshop given by Luís Vieira and Rute Ribeiro, directors of the company A Tarumba and of the Lisbon FIMFA Festival. A two-week workshop that was run together with the Portuguese puppeteer Paulo Duarte, for young theatre students from the University of Montpellier.

Presentation of the Workshop by A Tarumba

Presented to the Conference audience by Didier Plassard, Luís Vieira and Rute Ribeiro explained that their initial idea had been to make a selection of texts from very different periods, but that they had decided to use only those by Fortunato Depero (1892-1960), an Italian artist who was a member of the Futurist movement.

Image from the workshop presentation. Photo by the company

Specifically, they chose a text titled: Suicides et Homicides Acrobatiques. Drame Plastique Futuriste en Quatre Parties. They considered that the avant-garde form of the text allowed them to make a freer adaptation, opening up broader possibilities for the artwork and dramaturgy with the students.

Image from the workshop presentation. Photo by the company

At the end of the presentation, the audience were treated to a little surprise, inspired by some of the characters from the play Romeo and Juliet… 300 years old, by Edward Gordon Craig, with articulated cardboard pictures of none other than Max Reinhardt, Francis Bacon, William Shakespeare and Craig himself.

What was interesting about the group of students who had signed up for the course, all from very different cultures and widely separate countries (young people from Russia, Syria, Argentina, Bolivia and France), is that they had no experience of working with the language of puppetry, which meant they began by learning how to manipulate different kinds of puppets.

Image from the workshop presentation. Photo by the company

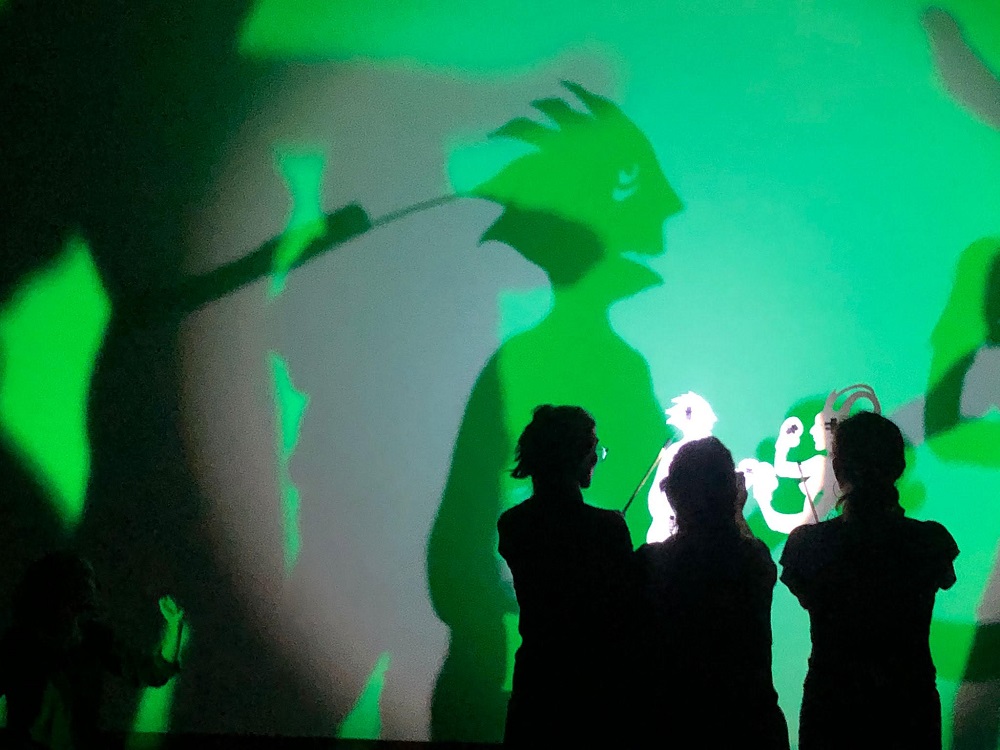

In the end, they opted to focus mainly on shadow puppet theatre, for obvious practical reasons given that the necessary construction could be carried out during the workshop hours.

Image from the Workshop by A Tarumba

The results were shown on the evening of Friday 15 October, with images and animations that produced a considerable impact on those present, while leaving students, teachers and organisers very satisfied.

The participants, with Luís Viera and Rute Ribeiro in the foreground. Photo by the company

The writers’ point of view

Four authors took part in this meeting with the participants of the Conference. All four had distinct experiencias with puppetry:

The authors during the presentation

Hervé Blutsch, author of about twenty plays, among others Anatole Felde (1995), Gzion, (1998), La Vie burale (2009), Scènes de la vie ordinaire (2012).

Patrick Boman, novelist, great traveller and playwright, whose plays include: Planète impossible ou Tatou (1985), Manger ours, manger chien (2006), Till Eulenspiegel, Polichinelle couronné (2008), Opéra polar.

Jean Cagnard, poet, novelist and playwright, writer of the plays: Des papillons sous les pas (2000), Les Gens légers (2004), L’Entonnoir (2007), À demain ou la route des six ciels (2010), Où je vais quand je ferme les yeux? (2015).

Catherine Zambon, actor, stage director and playwright, with titles such as: Samain (1999), Les Balancelles (2002), Les Terres fortes (2005), Œil pour œil (2012, con Jean-Philippe Ibos).

Patrick Boman, a veteran writer who had never before written for the theatre, entered the world of puppetry through the ‘clan Recoing’, as he said in his talk, having the well-known puppeteer Alain Recoing (1924-2013) as his neighbour. Together with him and his son Blaise Recoing (who created the Théâtre aux Mains Nus), he wrote his first plays for puppets. The other authors who took part in the round table came into contact with puppets through the meetings between playwrights and companies organised by La Chartreuse, the above mentioned Centre national des écritures du spectacle, located in Villeneuve lez Avignon. This institution has been hugely important in developing new dramaturgy for puppet theatre.

For these authors, who had no prior knowledge of puppetry, participating in these laboratories of exchange and mutual knowledge, organised by La Chartreuse, signified a ‘before and after’ in their work, discovering a new world that provided them with many teachings.

For Catherine Zambon, working with puppets has been an exercise in adapting to a world in which the word has a different role. She very much enjoys developing the more literary aspects of dramatic writing, but with the puppet she has had to limit herself to other conventions that demand the simplification of language and the search for verbal economy. For Zambon, this has perhaps been the most important thing puppetry has given her.

Image of ‘Les Balancelles’ by Catherine Zambon, directed by Alain Gautre. Photo by Jean-Paul lozouet

For Jean Cagnard, putting Matter on stage is one of the most pleasant surprises afforded by the world of puppetry. To see that everything can be brought to life, can be animated, has been like an explosion of wealth that has broadened the world of what is possible in theatre. Equally, Poetry plus this characteristic of objects and puppets as embodied metaphors, is the other great contribution to his work.

Image from ‘Où je vais quand je ferme les yeux?’, by Jean Cagnard, co-directed by Sylvie Baillon and Eric Goulouzelle. Photo by Veronique Lesperat-Hequet

Hervé Blutsch, whose theatre has a comic tendency, explained that when he works for a puppet company he generally begins from certain technical aspects that condition his options and are thus his true point of departure. Also, he has observed that the puppet, accompanied by himself or the puppeteers, allows him to develop a language that is, in part, more naturalistic but which nevertheless opens up possibilities so that the fantastical can burst though and a new world appear; as when the actor/puppeteer is marionettised, for example, and allows the other figures in the show to attack and ‘inhabit’ him/her, re-emerging in an ectoplasmic-puppeteer guise.

Image of ‘La vie burale’, by Hervé Blutsch

Patrick Boman, for his part, explained that his only experience with puppets has been with the traditional glove puppet, where everything occurs in the framework of the puppet booth. For him, writing for puppets has been a liberating experience as he realised that it offered an unusual freedom to be able to speak about everything without censorship, showing life in all its crude reality. Puppets can speak about, and show death or fornication without the least restriction. For him, accustomed to the obligatory political and cultural correctness demanded nowadays in ‘serious’ literature, writing for puppets has represented a ‘letting go’. Although he pointed out that this ‘letting go’ does not apply to the word, given that the language of traditional puppet theatre requires extreme containment, and if there is one thing that puppetry has taught him, it is to write under the imperative of radical verbal economy.

The meeting between the four authors was full of juicy anecdotes and a variety of specific cases; and the audience were delighted by the playful but modest tone of these writers, who were so pleased to have discovered the world of puppetry, which has offered them so much.

The critics speak

The Conference organisers left for the final course, as it were, the round table featuring the Critics, four in total, who spoke on Saturday night. They were: Mathieu Dochtermann, from France; Mascha Erbelding, from Germany; Oliviero Ponte Di Pino, from Italy; and myself, Toni Rumbau, from Spain.

Didier Plassard at the critics’ table

Mathieu Dochtermann, a critic who writes in the magazines Manip, Toute La Culture and La Gazette des Festivals was astonished at the quality and density of the Conference. He said he would not talk about the content of the three extremely interesting days, which included themes such as the contexts in which new writing for puppetry is generated, or the relationship between political theatre, Agitprop and the puppet, or the satirical liberty in puppet theatre throughout the centuries, etc. On the other hand, he did want to talk about what was not spoken of.

Image from ‘La Gazette des Festivals’

He referred then to the list of authors studied during the conference, which contained forty-three names, of which only two were of women and even one of these, George Sand, was considered not as an author writing for puppets but as the mother of Maurice Sand. Good critic that he is, he said that gender equality had not reached this conference, and he lamented the invisibility of women as playwrights for puppets. He recognised that this invisibility is open to remedy, if the names of the many women puppeteers who write within the companies were added to the list.

Mascha Erbelding, chief editor of the German magazine Double, on Puppets, Figures and Object theatre, said how amazed and impressed she was by the La Chartreuse in France, which has managed to arouse the interest of contemporary writers in puppet theatre. How could we do something similar at a European level? And she highlighted various qualities evinced by puppetry today, capable of speaking about philosophy, of delving into the poetic dimensions of objects and their silence, and of revealing their metaphorical, antithetical and spectral qualities.

Image from the web of Double

Mascha Eerbelding was very interested by questions such as: what language does the puppet speak? or, what language should it speak? These questions were not answered, and the matter remains open. She valued the fact that writers have entered the companies’ worlds in order to approach the reality of their specific languages. To end with, she referred to the gaze of the child and the naive point of view, a dimension that puppetry should explore further and with greater insistence.

Oliviero Ponte Di Pino, an Italian editor and the creator of ateatro.it, the webzine about theatrical culture, acknowledged that he was in no way a specialist in puppetry and that, rather, his field is theatre. He stated, however, that his magazine sometimes addresses puppet theatre, as in the monographic edition from 20 years ago dedicated to ‘Teatro di Figura’. He expressed a feeling of particular responsibility as an Italian, hearing the words Pulcinella, Arlequino, commedia dell’arte, and even Futurismo – all such Italian subjects – so often during the conference.

Extract from ateatro.it, the theatre culture webzine

Something which interested him very much from the beginning was learning about the puppet’s contemporary relevance, with themes that have often come to the fore, such as: intertextuality, and the aspect of being an intermediary as a puppeteer or one who writes for puppets; seriality, which Pulcinella is very familiar with; and the political dimension commented on by Mathieu Dochtermann.

While he listened to the talks, Oliviero Ponte Di Pino thought about all that the puppet has been for him and that broke down the wall of his indifference to this world. He thought about Bread and Puppet Theatre, and the giant marionette that has walked across Europe, Amal, who has given voice to the refugees of the world, with such a strong political message. He thought about Tadeusz Kantor and the fundamental subject of life and death present in The Dead Class; and about the works of the company Señor Serrano and their different levels of animation.

In his conclusion, Oliviero Ponte Di Pino referred to a statement he had heard the previous day, about how puppets allow us to explore the human by means of the non-human. It strikes him that, in our day, something is happening that the new dramaturgy for puppets also manages to do. There is a necessity to explore the non-human with the human, which is to say, to change the perspective, to turn the subject on its head. The world has changed. For example, we are speaking simultaneously, here in Montpellier and in Barcelona, and this obliges us to ensure that the theatre, which is still human, can help us understand the world of the non-human that we are entering.

For his part, Toni Rumbau, which is to say myself, in my condition of ‘voyeur’ of shows and after listening to the lectures from a distance given that I was unable to be in Montpellier for the Conference, spoke about what puppets seem to represent at the current time: an attempt to revitalise this function that the theatre has always had, of being a mirror for society. A mirror that perhaps needs other mirrors placed at its heart in order to refresh old contents and bring words and theatrical discourses out of their ideological univocality. Such surely is the function of contemporary puppet theatre, to be a creative engine of a dramaturgy of detachment and mirroring and, therefore, committed to experimentation and the revelation of doubles.

However, such experimentation cannot be ‘experimental’, unless it wishes to fall into the tautological loop of mere cultural interrogation. Puppets, objects, images and so many other meditative devices, are the mirrors that we place opposite the actor, or opposite the words themselves, in such a way that their reflections conjure up other meanings, not in order to view them repeatedly, but so as to create ‘other’ situations of an emancipating catharsis.

Image from ‘Untold’, by UnterWasser. Photo by Marco di Giuseppe. Festival IF Barcelona

I ventured to say that perhaps this change of direction, from an older form of puppet theatre towards today’s most contemporary puppetry, is a symptom of, or response to, a necessity of our time, by which I mean a need for the creation of mechanisms of self-observance: to see ourselves from a distance in order to know who we are, what we want, and where we are headed. Hence the importance we give to those other mechanisms or dramaturgical concepts such as silence, the void or emptiness, as if we wished to listen to Time itself and see its hidden directions, or the directions we would like to take, or simply to stop and not have to think about anything. To question matter, in order to perceive time and convert it into the mirror of transformations, a threshold we must cross.

Through its lecturers, the Conference spoke about all these things. A Conference that provided, with unqualified success, a brilliant procession of different dramaturgical features offered by writers who, from the 17th century to our own day, have written for puppet theatre in this western corner of the European continent.