If you never had the chance to see Christian Carrignon’s conference-show about object theatre, you may think this is a too wide topic. In fact, Carrignon himself starts his conference saying he is going to talk about his own experience rather than all this scenic form in general, because, he ironizes, “no one knows what it is”. Carrignon is the artistic director of the company Théâtre de Cuisine with more than 30 years as a puppeteer. Although anyone can see this conference or a part of it on internet (see it on this same article), it is worthy to comment some highlights.

Under the title ‘Théâtre d’objet: mode d’emploi’ (‘How to use the object theatre’) one can see a very peculiar show made with excerpts of others and performed by Christian Carrignon himself. The first thing he does is framing the space where the conference is going to take place, because one of the main arguments he presents is that object theatre has a lot to see with cinema.

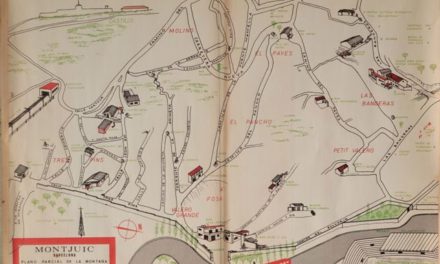

1. The set

“The space in object theatre is changing all the time. It is very difficult in theatre to be inside Macbeth’s castle, for example, where you can see Lady Macbeth and Macbeth, they have an appropriate light, and all of a sudden be outside the castle. At least for me it is not easy to pass from one place to another, but object theatre allows you to do this in a very similar way than cinema, but with much cheaper resources.”

'Théâtre de cuisine' ('Kitchen theatre'), by Christian Carrignon.

The first scene he performs in his conference —or at least the version I saw— is taken from his own show ‘Catalogue de voyage’ (‘Travel catalog’). In this, he plays the role of a tourist and mountain climber, but also his wife or companion. An adventurer toy, Action Man or Big Jim, hanging with electric wires from the puppeteer’s body makes the scene visible —so it happens— while Carrignon performs a dialog just by looking upwards or downwards. With this simple gesture and standing on a chair, he is playing two different characters that are supposedly in different places, one upside the mountain, the other one down.

2. The movies

“The principle of the film editing is to help the audience to understand the story. The goal is to choose what is important and show it consecutively. In object theatre, as everyone can see the whole set all the time, the actor must help the audience to edit the happening. It means to focus on what he wants the people to see.”

“The object theatre is like movies turned into a performance. Cinema is its main predecessor. Both forms use the lights and the editing to create the structure of the story. But actually object theatre is born around 1979-1980. (1) As far as I know, the first show is ‘Small suicides’, by the Hungarian puppeteer Gyula Molnár (see also this article).”

3. Recognition of the objects

“To make object theatre work out, the audience must recognize the objects immediately. A feeling of self-recognition through the objects must arise from the very first moment. This type of theatre is perfect for this, because the objects commonly used can be purchased in any shop and found in all homes. For example this.”

He shows the binocular slideshow he used in his first performatic example, the kind of bizarre souvenir that anyone may have seen in an aunt’s home.

Objects in this theatre are never what they used to be for.

“The object used in this theatre”, he continues, “which is normally a manufactured object, is a kind of palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment where the first writing has been erased and it has been re-used for a newer manuscript. So you can have the impression that something of the older writing remains. I think object theatre works a little bit this way too. Once you recognized this little souvenir, it can be used for a new purpose and it will never ever be a souvenir again.”

“The origin of the object theatre is around the decade of 1980’s and this is not a casual thing. Those years were the end of what we call in France the “Trente Glorieuses” (“the Thirty Glorious Years”, the period of economic growth between the end of World War II and the decade of 1970’s). This is the end of welfare. By then, everyone had already bought a car, a television and lots of consumer goods. In fact, by the 80’s people starts to think that all those goods do not necessarily mean welfare. I think this is the reason why object theatre starts, as an irony on possession and on our society. In France, people began to accumulate goods from World War I (1914-18), so there is a link between the need of accumulation and war, to the point that a disappeared man can be represented by the objects left behind.”

4. The metaphor

Christian Carrignon gives this example: “In the 1914-18 war, men in trenches used to drink red wine. No matter if they were Germans or French, everyone used to drink red wine because it was the way to forget a little bit their situation. Well, when the bottle comes out it is full, and if we see it as a metaphor, we can agree that the bottle is the soldier and the red wine must be his blood. Then, after an explosion, would you agree that an empty bottle is a dead body?”

One little story about this transfer between subject and object: “A very good friend of mine went to meet his brothers and sisters after their grandmother died. They all want to keep something to remind her —one of them takes one table, another one takes one cupboard, etcetera. He only takes the little bathtub thermometer his grandma used with him when he was a little child. He doesn’t want anything else, just that little thing he can put in his pocket. In some way, it is like bringing grandma in the pocket. When, later, he gets home, he puts the thermometer on the table and it splits. On a solid surface, as it is round shaped, it reminded a little the body of his grandmother. So then she died on his table.”

The second scene performed during the conference is taken from an exercise of one of his workshops. He ties the tip of a wool yarn to his toe and the other tip to a 7 centimeter tyrannosaurus-rex made on plastic. He is calm, but suddenly he starts screaming and plays being chased by that monster. Of course, this is hilarious, but at the same time the dinosaur seems to be alive for real, as the more he runs and pulls the yarn the more the t-rex is ferocious. Then he stops and takes one scissor and shows it calmly again to the audience with the tip of the blades pointing up, and says: “Papa” (“Daddy”). Then he cuts the yarn.

After this, he asks the attendants about the possible meanings and multiple answers come out: inner fears, the teeth of the t-rex as a synecdoche, the part for the whole referring to a real or imaginary threat, an umbilical cord cut by the presence of a very masculin father, etcetera.

A terrible monster tied to the actor's toe.

5. The ‘editing’

As he said at the beginning, the actor must help the audience to edit the story. This is why he shows the scissor in this example, and this is why he points at particular objects on scene. “There is no need of a special acting”, he says in the internet version of the conference. “I think pointing with one finger is enough to focus the action on one symbol. This is a straight lines and angles theatre form. Similarly to mask theatre, mime or clown, there are particular rules to play on scene that we use in object theatre too.”

A knife is just a knife until it becomes a cruel hunter chasing a rabbit and a deer.

The conference I saw has two more scenes: “The Little Rabbit”, in which Christian Carrignon plays two different characters, the rabbit and the deer, one inside a house and the other outside, with another weird souvenir from maybe Switzerland or a place like that: a little wooden chalet, surrounded with little plastic trees and confetti snow. In that scene, Carrignon shows the quick change of focus, as it also occurs in cinema. The audience is guided into a very simple metaphor: if his hands are deer horns, he is the deer (interior, day); if his hands are rabbit’s ears, then he is the rabbit (exterior, day), and a simple knife is a hunter. The repetitions of the scene are just another figure of speech that increases its drama.

The last scene is an exerpt from ‘Small suicides’ by Gyula Molnár, in which a little Alka-Seltzer becomes a stranger among candies, a living image of marginalization.

Note:

(1) In another version of his conference-show that you can see online, Christian Carrignon says: “We cannot stablish the exact date when the object theatre started. I think it was before 1979-80, but we know this name appeared for the first time in those years.” See it here: