The beginnings. According to the Turkish scholar “Metin And”, shadow theater moved to Turkey from Egypt in the 16th century after Sultan Selim 1st conquered Egypt in 1517. Ibn Ayass, the Arabic historian, narrates in his work, Badai’ az Zouhour[1], that Sultan Selim watched at the Rawda Palace a shadow play depicting the assassination of the deposed Mamluk Sultan, he called on the puppeteer and bestowed his graces on him. He then said to him: “When we go to Istanbul, you shall come with us so my son can watch and enjoy your show”.

Karim Dakroub, at the Simposium Polichinela in Barcelona. Foto: Jordi Parra / IT.

It is said that Shadow Theater came to Turkey from the Far East through Persia. However it is uncertain to this day how it arrived to the Arab countries, but certain facts lead us to believe that it goes back to the 11th century (and may be before) and we will present the arguments confirming this:

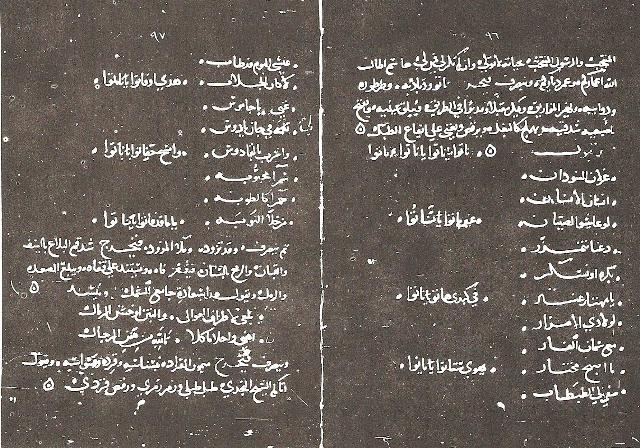

Manuscript Ibn Daniel.

- In the 13th century: the main references in that time are three texts, considered as the oldest Arabic theatrical texts, written for the shadow theatre by Shamseddine Ibn Danial in 1368. We have four manuscripts of these texts, two in Cairo, one in Madrid and the fourth is at the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul.

Old Egyptian Shadow - In the 12th century: After Salah ad-Din al Ayyubi topped down the Fatimids in Egypt in 1171, he attended with his vizier Al Qadi Al Fadhel a shadow play. At the time, banning Shadow Theater was being considered for religious reasons. Salah ad Din told the Qadi if it is illegitimate we won’t watch it. After the end of the show, the king asked him what did he thought of what he saw; the vizier replied “I saw a great preach, I saw states falling and others rising”[2]

- In the 11th century: Ibn Hazm (994-1064) described a shadow play as follows: “I have never seen anything more lifelike than the shadow theater, with its actors mounted on wooden handles that are turned rapidly so that some disappear and others appear”[3]. This important reference to shadow theater in Al Andalus denotes a developed type of Shadow Theater known at that time. Faruk Saad named it “The mechanical shadow theater“[4]. Al Ghazali[5] (1059-1111) and Abul Alaa’ Al Maarri[6] (973-1157), in some of their writings, describe their impressions of a shadow play. Al Masbahi (977-1029) also describes a shadow theater show in Egypt saying: “People in Egypt usually go out on holidays and parade in the streets holding figures and puppets“.[7]

Old Egyptian Shadow - In the 9th century: There is an indication in the book of As Shabushti “Ad Diyarat” (d. 998) of the presence of shadow theater in Iraq, the poet Daabal Al Khuzai (865-960), has threatened one of Al-Ma’mun (the Abbasid caliph) cooks that if he satirized him he would “get his mother on a shadow theater show“[8]. This indicates that Shadow Theater was widespread in the Abbasid era and that shows were of satiric nature.

- In the 8th century: The oldest indication of shadow theater in the Arab World goes back to Imam Shafi’i (Gaza 767-820) in a poem cited by Mohammad Khalil Al Moradi (1871)[9]: “This world for me is a shadow play moved by The Merciful Lord“

(أرى هذا الوجود خيال ظل محركه هو الرب الغفور)

But how did Shadow Theater attain the Arab World before that period?

Old Egyptian Shadow

Probably, it was brought by merchants trading with the Far East and namely Java[10], between the 7th and the 9th century[11].This form of art has been known on the island as a big tradition for a long time before. Other say that it was brought from China by eastern Turkish tribes to Persia and then to the Arab world[12].

The religious dimension

During the Fatimid rule, the caliph allowed all forms of art to develop and prosper. This led to the reappearance of old traditions in the conquered states, notably the Egyptians[13], like the traditions of believing in a medium, in which the Fatimids themselves believed. In this atmosphere, the puppet becomes the medium between the human and the invisible world, the world of spirits and djinns (this is a characteristic of the shadow art in its original birthplace in East and South East Asia).

A connection between art and religion might not stand true in any place or epoch as much as in the Islamic world, here and according to the metaphorical phrase of Roger Garaudy “All forms of art lead to the mosque, and the mosque to the prayer[14]“.

The puppet in itself represents this philosophy of faith following which all creatures are puppets in hands of the Mighty Creator. The puppets of the shadow theater are a symbolic reflection of whom they represent without being a traditional direct personification of the created human appearance as personification is prohibited as the artist might be in doubt that he is able to insufflate a soul in it. Metin And says that the deformation of the characters in shadow theater is related to the prohibition of human representation in Sunni Islam[15]. For these reasons, maybe, Shadow Theater was more accepted than other artistic forms such as painting and acting since it didn’t rely on depicting all the human body directly but through deformed shadow reflection.

Old Egyotian Shadow.

In Sufism and mystical philosophy, as in Suhrawardi for example[16], light and shadow are an abstract representation of two opposite worlds, the spiritual world facing the real concrete world. Light and darkness are therefore two symbols: a symbol of happiness in the spiritual realm and a symbol of misery in the “evanescent” world[17].

Old Egyotian Shadow.

This is not far from the historical conditions during which Shadow Theater entered the Islamic world, when Sufis movements and ideas were on the rise in times of gloomy social and political conditions.

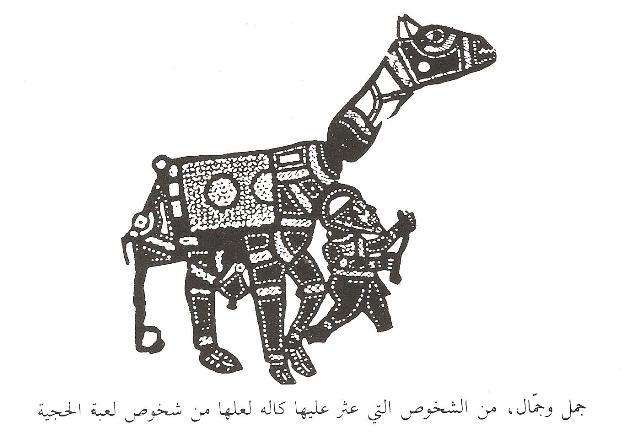

It is noteworthy to mention that most of the shadow puppets plays in Egypt during the Mamluk period have the traditional ending: the repentance of the characters and their pilgrimage to Mecca to do Hajj and ask for forgiveness.

Subject of puppet plays in different Arab countries

Egypt

Egypt was among the most fertile lands for shadow theater play scripts, we have received many texts and characters through the works of European orientalists and some Arab scholars. Among the famous play scripts:

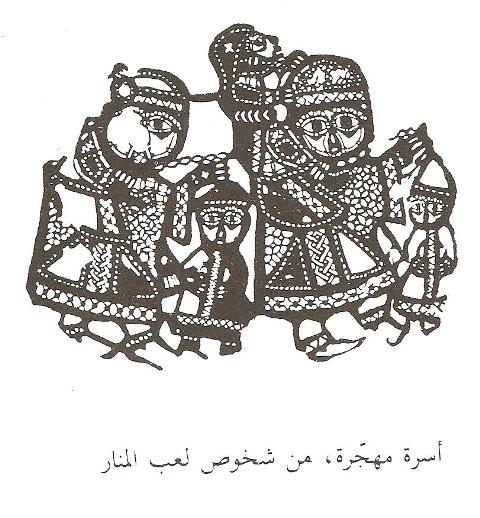

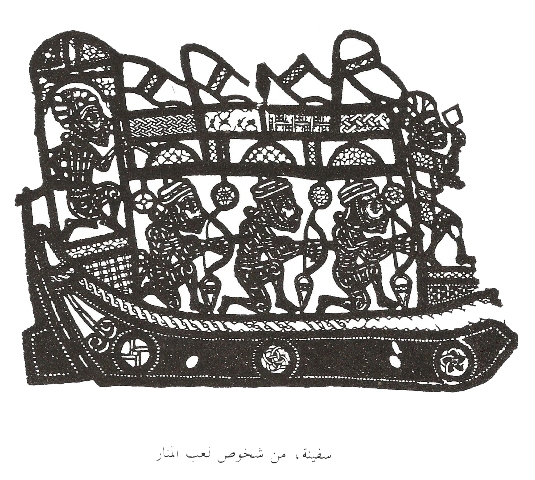

The Play of the Old Lighthouse (Al manar al qadeem):

This is a long text published by Paul Kahle, it was written by more than one author over a long time period, it tells about battles during the crusades. All the text is a rhymed dialogue between two characters Al Haziq and Al Rakhim (somehow, similar to Karagöz and Hacivat – Karagoz and Iwaz) the first is a coward and the second tries to convince him and involve him in the war. Through the text, we see battles with battleships and swords. The main indication for the battles is the lighthouse of Alexandria. It is said that it was this play that Salah ad Din saw and liked.

Old Egyotian Shadow.

The Play of the New Lighthouse (Al manar al hadeeth):

We see the same two characters, Al Haziq and Al Rakhim, in different events, it all start with lazy carpenters, who are late in building the battleships, unconscious of the threat of the Franks, these soon arrive and destroy all the battleships. The situation is saved by “al Ghorab Al Mansoor” (The victorious crow) who destroys all the battleships of the enemy. The play relies on detailed scenes of war. Paul Kahle published it in german and Arabic, it was republished in Arabic by Fuad Ali Hassanein.

Old Egytian Shadow.

The play of Al Sheikh Taleh:

The story begins with the sheikh Taleh conspiracy with his slave girl. She is to seduce the head of judges, so he can approach him and be appointed judge. We know later, that he had done the same in several places and each time he had to flee and change his residence after he was discovered. At the end of the story, the conspiracy is revealed and he repents and goes to Mecca for forgiveness[18].

Old Egyptian Shadow.

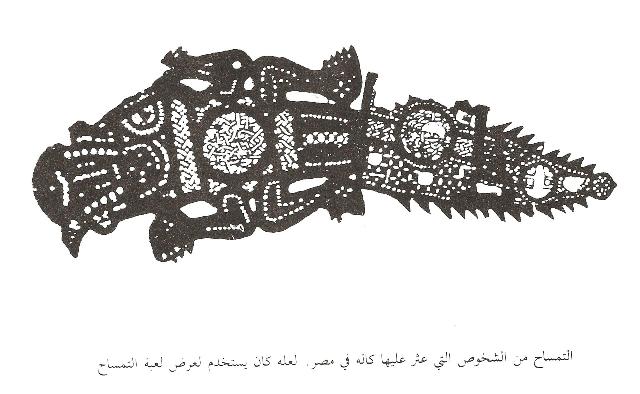

The play of The Crocodile:

It tells the story of Zaberkash the farmer who laments over his bad luck. He is called by a sheikh to become a fisherman, but his new craft doesn’t change his bad luck, until he is swallowed by a crocodile. And everybody gather to save him.

Old Egyptian Shadow.

The play of Alam and Taadeer:

A very long text, similar to a series, it can be played over several nights, exceeding seven. It tells the love story between a Muslim young man Taadir and the daughter of a Christian monk Alam, after many adventures, she surrenders to his love, convert to Islam and they both go to Mecca for Hajj.

Old Egyptian Shadow.

The play of The spirit of Shadow (Tayf al khayal):

The most important and original play-scripts for the shadow puppet plays, the trilogy of Shamseddine Ibn Danial al Mosuli (1238-1310), who fled al Mosul (Iraq) to Egypt during the 13th century Mongol invasions (1258). These are considered as the oldest play-scripts in Arabic.

To the difference of other shadow theater plays, these were not only improvisations but texts written in dialogues, a form unknown previously in the Arab culture.

The three plays are different, in form and in subject. The first one is built on a series of misunderstandings similar to the “farce”. It tells the story of prince “Wisal”, who is looking for a bride with the help of a wicked matchmaker, she finds him a bride and once married he discovers that his wife is extremely ugly contrary to the description of the matchmaker. The story ends with the death of the matchmaker and the repentance of the prince and his pilgrimage to Mecca. The plot is simple, but it is mainly characterized by the references to the political situation in the country. It apparently praises the measures and hard sanctions imposed by Baibars, the reigning sultan at the time, against all whom he accused of dissoluteness under the pretext of maintaining security in the country to fight the enemy outside. Ibn Danial, criticized these reforms, he presents a play highly obscene full of homosexuality in text and action. He ends the play by calling his characters to repent by performing the Hajj to Mecca.

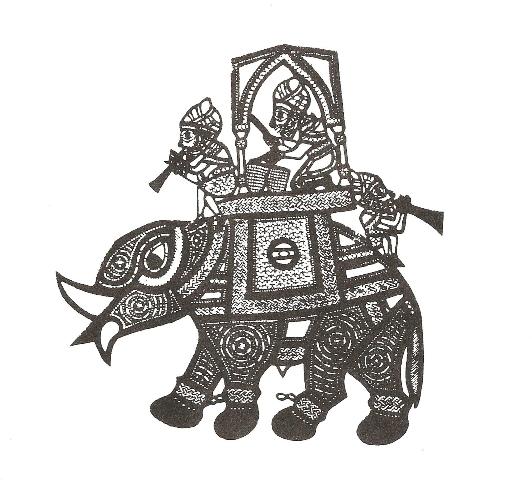

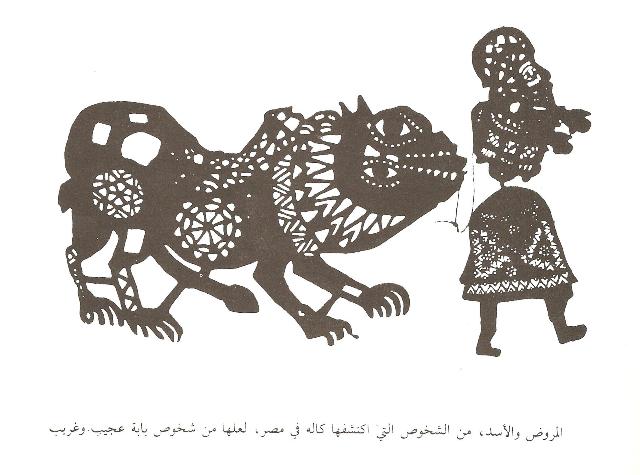

The second text is “Ajeeb wa Ghareeb”, is radically different, it is a circus like show, composed of several acts, juggling, magic, animal taming and other performances uniquely depicting popular scenes in Egyptian marketplaces under the rule of the Mamluk. Ibn Danial ends this second play by the repenting characters journey to Mecca as in the first one.

The third play, “Al Mutayyam wa ad Da’i al Yatim” (The infatuated and the lost orphan), is dissolute far beyond the limits allowed in that period. It tells the story of the infatuated who does all he can to please his lover including cockfights, ram fights and bullfights, until the end of the play where there is a ceremony with all kinds of sexual perversions, then at a certain moment a deafening sound is heard, the angel of death appears, he has come to take the infatuated. The latter asks for some time so he can go to Mecca and repent (just as in the other shadow plays).

Syria:

Despite several indications to the presence of Shadow Theater in the 13th and the 15th century, it is clear that the main period of prosperity of this art was in the 19th century, in Damascus, Aleppo and along the coastline, as a result of the influence of the Turkish Karagoz Theater. It is mainly about the typical characters of Karagoz and Iwaz (Karagöz and Hacivat). Karagoz represents all kind of people with good and evil inside them; he is a merchant, a worker, naïve and idiot sometimes, whereas Iwaz is malicious and loves pranks.

Shadow Theatre at Azem Museum, in Damascus.

Syrians have adopted the Turkish characters and some of its topics, but most of the topics of the shadow theater in the Levant were inspired by the problems of everyday life, to the extent that Karagoz Theater has been used as a satire to instigate the people against the Turks and call for Arabic culture and traditions.

Syrian Karagöz and Hacivat.

The particularity of the Syrian shadow theater with respect to its Turkish counterpart is in borrowing some features of the Syrian Hakawati traditions (the storyteller). Several puppeteers intended to include these traditions in their shadow plays to attract the public, because at that time people were really attached to the storyteller phenomena. People who frequented coffee shops waited for what was called chapters of war, these were stories presented after the acts of Karagoz, with historic characters such as Sayf bin zi Yazan and Antara bin Shaddad but also characters from legends and popular tales among which are djinns and devils taken from the popular legends such as Fadous Abu as Sabeh Rous (The seven headed Fadous)[19]. These stories of wars extend to include the Persian war, the Ghassanids war, wars in the pre-Islamic period and wars in Islamic periods. All this is narrated without any historical chronology, it starts with the war of the infantry, then a duel between two cavaliers and at the height of the battle djinns, monsters and legendary creatures intervene and the war ends in magic.

Many texts were assembled, they are to a certain extent similar to the Turkish Karagoz texts, and some are copied from Turkish, such as the chapters of establishment, The Hamam and the wedding.

Most of the shadow plays characters, especially the Karagoz and the chapters of war are kept at The Azem Palace museum in Damascus.

Lebanon:

Shadow theater in Lebanon and Palestine is related to the Syrian tradition because of the geographical interconnection and the sociopolitical unity at that time. Shadow theater used to show in coffee shops in Beirut, Saida and, Tripoli. Enno Litman, the orientalist, recorded seven texts that were widely shown during that period, these are: The beggars, Ifranjun, The Afiouni, The Hamam, The evening, The wooden logs, Amon. These are acts similar to the Syrian ones.

Algeria:

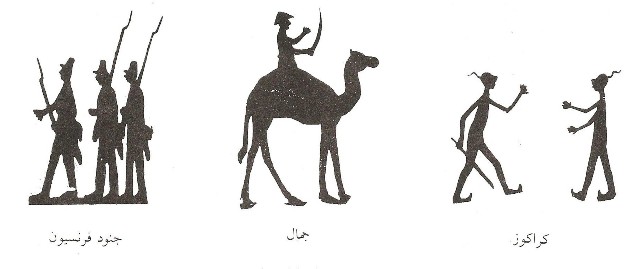

The Algerian shadow Theater is quite particular because it used the main character, Karagoz for goals related to resistance to French occupation.

Algerian Shadow.

Probably the most famous and funniest Algerian shadow play is the one seen by Puckler – Muskau[20] in 1835 in Algiers. He mentioned a specific scene where a giant Karagoz confront the French troops with his penis and tear them into pieces. This is probably the scene that led the French colonial forces to prohibit shadow plays in Algeria for a long time.

In 1863, Maltzan[21] saw, in Constantine, another kind of shadow plays, one where Karagoz is flirting with a girl, her mother appears and sees them in an indecent position, she scolds them but Karagoz then turn to the mother and starts flirting with her. The mother then calls on her mother and Karagoz again starts flirting with the grandmother and she likes it.

In another type of shadow play, Gaston Baty and René Chavance[22] mentioned shadow plays in Algeria inspired by the thousand and one nights, without further details.

The published texts are Karagoz and the French troupe, The devil in French clothes, The love affairs of Karagoz, Karagoz varieties, Inspired by Thousand and one nights.

It is noted that in Algerian shadow plays the main character is Karagoz without the accompanying character Iwaz.

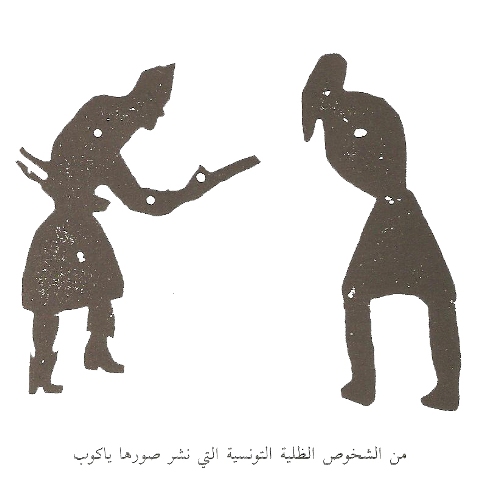

Tunisia:

As far as we know, Tunisia knew the Shadow Theater after Turkey; we didn’t get anything from Tunisia before the 19th century.

Tunisian Shadow.

There are similarities between Tunisian and Algerian plays with different versions of the same topic. However, it is noteworthy that certain plays have topics that resemble greatly Turkish shadow plays such as The swing, The Hamam and The bride…

Tunisian Shadow.

It is also interesting to mention that in all Tunisian plays Karagoz and Haji or Haziwiz are inseparable.

The puppets however are really primitive especially in comparison with Turkish, Egyptian, Syrian and even Algerian ones.

From Tunisia we have seven play-scripts: The swing, Hindawi, The bride, The Lemon, Al Hamam, The boat and, The fish.

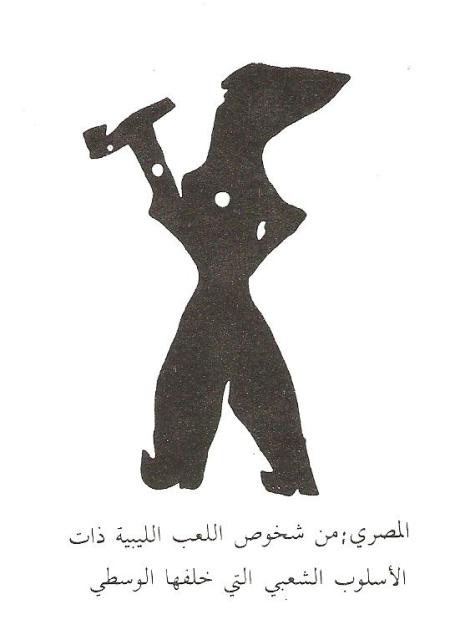

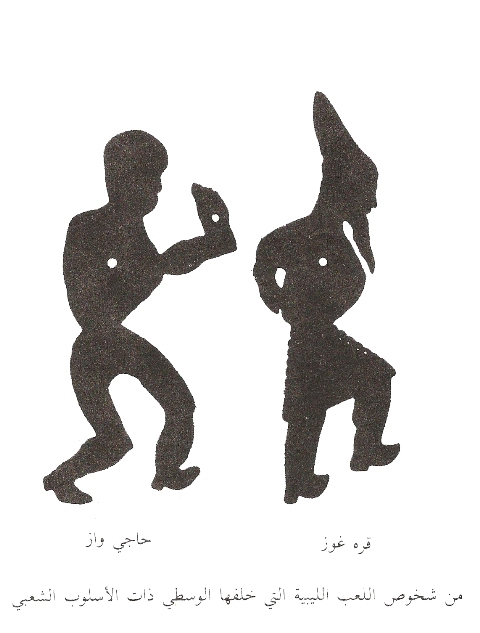

Libya:

Wilhelm Honerbach published Libyan play-scripts he had taken from Mohammad al Wasati, the puppeteer. The publication of these texts allowed them to be known on a wider scale and to compare them to other scripts from Algeria and Tunisia.

Lybian Shadow.

As in Tunisia, the main characters are Karagoz and Haji wan, we have until now 10 play-scripts: The Hashish smoker, The bride (similar to the Tunisian text), The waterwheel, The Hamam, The boat, The scribe, The vat, The ogress, The arcade, The servant with the broken leg.

Lybian Shadow.

Morocco:

The only information we have about Shadow Theater in Morocco is what Landau[23] mentioned about some wonderful shadow plays that were presented in Marrakech with topics inspired by the thousand and one nights and animal legends.

The artistic styles of the puppets:

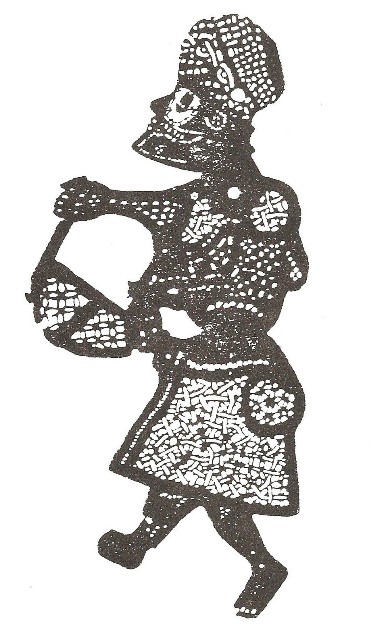

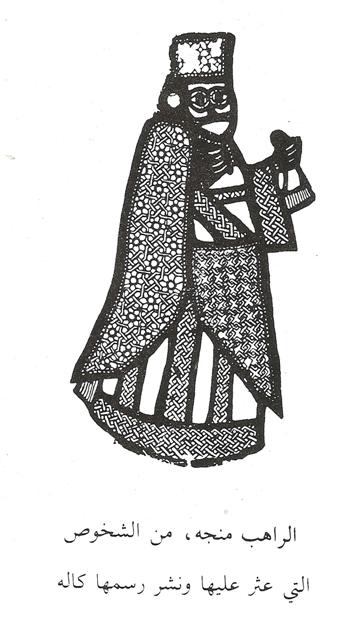

We can classify the characters of the Arabic shadow theater in four categories according to their style: The Mamluk style, the Ottoman representative style, the Arabic popular drawing style and, the primitive or particular style.

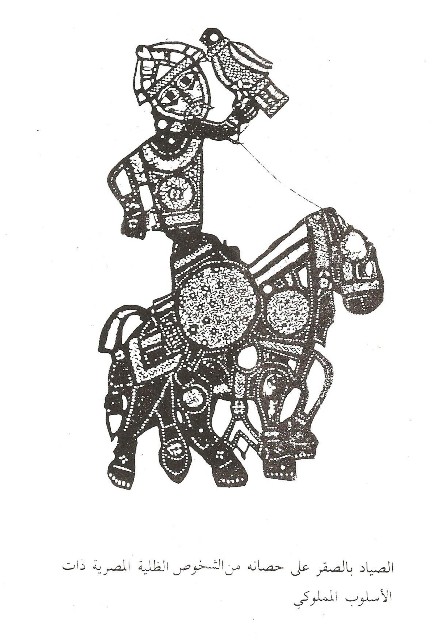

The Mamluk style:

Paul Kahle was the first to discover this type of characters. He relied on the coat of arms of the Prince guardian of the Palace in Egypt, who lived in the 13th century. We can say that the character drawings pertain to the Mamluk illustration arts that distinguished manuscripts of that period with their miniatures, as well as other illustrations found on tableware, clothes and other personal effects.

The main features of this style are the exaggeration in decoration and ornaments whether in design, drawing or perforation. The elements are drawn in decorative shapes formed of interlaced lines.

Moreover, the Egyptian characters discovered by Paul Kahle are marked by a sophisticated and luxurious design, the elements are simple and limited, the characters are large in size, especially their eyes, their movements and emotions are few.

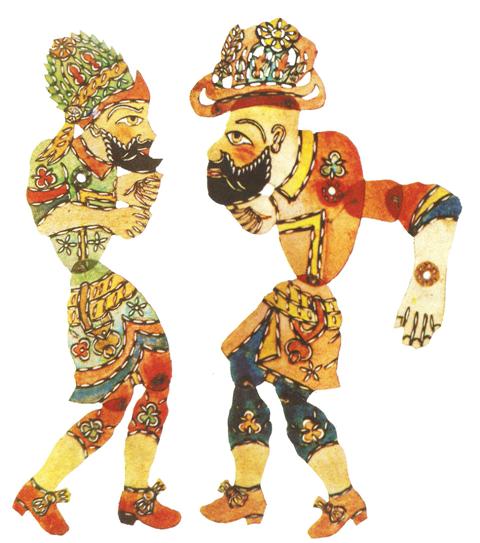

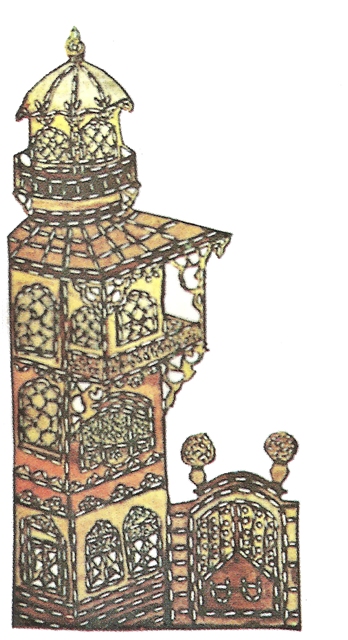

The Ottoman style:

This style is shown in characters dating back to the Ottoman period. The shadow theaters in Syria, Lebanon and Palestine were the ones mostly influenced by this style. The design, drawing and colors of the characters show a direct presentation of the topic, with its basic features only, all empty areas are filled with colors, and lines are marked by perforations.

Turkish Karagöz and Hacivat.

There are some differences in the perforation style between Syrian and Turkish characters. Turkish artists usually draw a long line and perforate it evenly; the perforations then appear as a discontinuous line. In Syrian characters, these lines totally disappear; they are replaced by patterns and decorations following the Arabic popular style.

Turkish Gostermalik.

Characters of Arabic popular drawing style:

At the end of the 19th century, the popular drawing style for characters prevailed, especially in Lebanon, Syria and, Palestine. The popular style is that found in illustrations tattooed on human skin, on paper, on textile, on certain tools or on walls. These drawings usually do not respect the anatomic proportions of the human body or the proportions of other objects, there is also no respect whatsoever of perspective rules. This style adapted to each country according to the local taste, hence the difference between the forms of the characters across the Arab countries from Syria to Algeria.

Characters of primitive or particular style:

If we looked at the Libyan and Tunisian popular characters we will notice that they are primitive, they nearly look like children drawings in their shapes. They are extremely simple, without colors or perforations. We only see the outer form.

On the other hand, the Algerian characters are different. For some reason they were influenced by the paper cutting art and Parisian shadow puppet characters of the 19th century. It is not unlikely that Algerian puppeteers have seen French puppet shows, because of the intensive influence of the French colonial culture on the Algerian society. The characters are finely drawn and cut, without perforations, well crafted, they are long and thin, very well made with small faces with respect to the body. Well designed with expressions reflecting the nature of the character.

Shadow theater today:

It is sad to say that traditional shadow theater is completely extinct in many countries, such as Lebanon, Palestine and Algeria. It is on the way to extinction in Syria and Egypt, where the last of the popular puppeteers are dead. There were no initiatives in these countries to revive this art, except through the efforts of few individuals who were not able to spread their ideas.

[1] Ibn Ayass, Badai’ az Zouhour, the vents of 923 H., (vol. 3 p. 125 of the Arabic edition)

[2] Alau’ddin Ghazouli, Matali al Boudour wa Manazil as Sourour (vol. 1 p. 78 of the Arabic edition)

[3] Ibn Hazm, Al Akhlaq wa Assiyar, (Arabic edition p. 14)

[4] Saad, Farouk: Khayal Al Zill Al Arabi (the Arab Shadow Theater). Ed. Charikat Al Matbouaat, Beyrouth 1993. p. 291

[5] Al Ghazali, Ihya’ Ulum ad Din (vol. 4 p. 122 of the Arabic edition)

[6] Abu al Alaa al Maarri, Al Louzoumiyyat aw Louzoum ma la Yalzom, (p. 104 of the Arabic edition)

[7] Al Masbahi, Lata’if Al Hikma (p. 516 of the Arabic edition)

[8] Shabushti, Ad Diyarat (p. 188 of the Arabic edition)

[9] Al Muradi, Silk ad Durar (vol. 1 p. 132 of the Arabic edition)

[10] Tueedleyand & J. Reeves. A history of Theater

[11] AND, Metin. Karagoz – Turkish Shadow Theater. Ahmet Rasim Çankaya. Ankara 1975.

[12] Hamada Ibrahim: Khayal Al Zill Wa Tamthiliat Ibn Danial (Shadow Theater and Ibn Daniel plays). Ed. Ministry of Culture, Cairo1963 p. 43

[13] Saad Saleh: Traditions of popular comedy. Ministry of Culture, Cairo 1994. P 80

[14] Saad Saleh: Traditions of popular comedy. Ministry of Culture, Cairo 1994.p. 79

[15] Saad, Farouk: Khayal Al Zill Al Arabi (the Arab Shadow Theater). Ed. Charikat Al Matbouaat, Beyrouth 1993. p. 201

[16] Hussein Mroueh, An Nazaat al Madiyya fi al Falsafa al Arabiya al Islamiyya

[17] Saad Saleh: Traditions of popular comedy. Ministry of Culture, Cairo 1994., p. 78

[18] Faruk Saad p. 202 (citing Mohammad Kamel Hussein’s book Min al Adab al Masrahi)

[19] Faruk Saad, p. 741

[20] Furst Puckler – Muskau: Semilasso in Afrika, I, S. 135

[21] H.V. Maltzan: Drei Jahre in Nordwestern von Afrika, III, S. 59-60

[22] BATY,Gaston et CHAVANGE,René. Histoire des Marionnettes. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris,1972. p93

[23] Landau, Jakob M.: Shadow plays in the Near East. Jerusalem, Palestine institute of Folklore and Ethnology, 1948.