Let us borrow this well-known phrase attributed to Galileo Galilei, after he abjured the heliocentric vision of the world before the Inquisition: And yet it moves… A phrase adopted for the name the International magazine published by UNIMA between 2002 and 2008.

Galileo teaching the Doge of Venice to use a telescope. Fresco by Giuseppe Bertini (1825-1898). Wikipedia

Galileo teaching the Doge of Venice to use a telescope. Fresco by Giuseppe Bertini (1825-1898). Wikipedia

Yes! The hiatus of 2020, and the successive waves of the pandemic that have swept the world, and continue to do so, have not put an end to the Performing Arts, or to the Puppet, Visual and Object Theatres of our sector (PVOT). They slowed it down, that is true, but the reactions of puppeteers have been so powerful and visceral that all those involved in the field – spectators, programmers, cultural politicians, artists, directors, constructors and the long etcetera of multiple disciplines that revolve around them – have given their all, and today the so-called PVOT (in Spanish, TTVO) is one of the sectors that can look most boldly and decisively towards the future.

These are not mere empty words or Christmas rhetoric; nor fatuous shouts of victory directed at a future we long to see more clearly and which everybody suddenly wants to buy into. No. Today, many artists and directors turn to this dramaturgy of distance, doubleness and reflecting mirrors, conscious of the new instruments they offer, allowing us to engage with the complex realities of our world.

The old systems of emotional identification, of unleashed passions that impel peoples and cities to fight one another, however gratifying to those who crave such things, run a short and disastrous course ending in self-destruction.

The world is currently so fragmented and polarised that practically all relationships require mediation. To mediate: to put something between one extreme and the other, between a truth that is true and its equally true opposite, between one fist and another fist.

Battle between two recalcitrant rams, in the Baroque Nativity Scene of Laguardia. Photo T.R.

Battle between two recalcitrant rams, in the Baroque Nativity Scene of Laguardia. Photo T.R.

To mediate: ‘to exist or be located between two people or things’. This is what puppet theatre does. By placing a puppet between an actor and a spectator, distance is created. The puppet becomes the mediator between different sensibilities and cultures. Almost by definition, the puppet creates a doubling; it becomes a mirror in which we see ourselves reflected. However, the curious thing is that, although it is a mirror with a single fixed surface, we all seem to be reflected in it.

Detail of the Gothic portico of the Church of Santa María de los Reyes, in Laguardia, in the Rioja Alavesa, where a beautiful animated Baroque Nativity Scene has been represented every Christmas for more than three hundred years (see here). Observe, at the centre, the effigies of the Three Wise Men on their way to adore the baby Jesus. Photo T.R.

Detail of the Gothic portico of the Church of Santa María de los Reyes, in Laguardia, in the Rioja Alavesa, where a beautiful animated Baroque Nativity Scene has been represented every Christmas for more than three hundred years (see here). Observe, at the centre, the effigies of the Three Wise Men on their way to adore the baby Jesus. Photo T.R.

It is the power of the effigy. (Didier Plassard defines puppet theatre as ‘théâtre d’effigie’. See his book L’Acteur en effigie, Figures de l’homme artificiel dans le théâtre des avant-gardes historiques, L’Âge d’Homme, Lausanne, 1992.)

Cover of the book ‘L’Acteur en Effigie’, by Didier Plassard.

Cover of the book ‘L’Acteur en Effigie’, by Didier Plassard.

Ed. Institut International de la Marionnette.

The effigy possesses the power of the symbol, of myth, and allows anyone to feel represented by it. It is a mirror that says much, but sometimes says nothing, remaining still, mute and mysterious. We collide, then, against this mirror of the duplicate figure that represents us but intercepts us. It separates us and stops us in our tracks.

Oedipus and the actor Jorge Valle who gives life to the character. Company Bambalina Teatre Transportable.

Oedipus and the actor Jorge Valle who gives life to the character. Company Bambalina Teatre Transportable.

Directed by Jaume Policarpo. Company photo.

This is why we always have to pass through the symbolic mirror and cross over to the other side. To see the hidden face, which is usually our own; that dark part of ourselves that we prefer not to see. Or something else. Who knows?

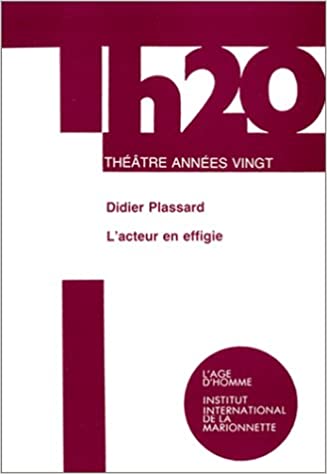

To go through the mirror is a contemporary discipline, inaugurated by the Englishman, Lewis Carroll, with his tales of Alice.

Lewis Carroll cleaning the lens of his camera. Photograph by Oscar Gustav Rejlander. Image, Wikipedia

Lewis Carroll cleaning the lens of his camera. Photograph by Oscar Gustav Rejlander. Image, Wikipedia

That Carrol was a photographer explains his obsession with mirrors. Are cameras not mirrors that fix what is reflected in them? A mirror that allows the photographer to enter the image, define its tonalities and, even, introduce into it spiritualistic ectoplasm or other ghostly presences from within his imagination. With his own such personal experiences, it is understandable that for Lewis Carrol, when explaining stories to his young friend Alice, it was perfectly normal to pass through the surface and see worlds hidden ‘on the other side of the mirror’.

Alice stepping through the looking glass. Drawing by John Tenniel. Image, Wikipedia

Alice stepping through the looking glass. Drawing by John Tenniel. Image, Wikipedia

The obsession with mirrors continues to haunt us humans. To discover the origin of our origins – what happened in that microsecond of the Big Bang – on Christmas Day, 25 December 2021, NASA, together with the European Space Agency (ESA), launched the James Webb Space Telescope, which is nothing more than a huge mirror that will orbit the Sun at a distance of 1.6 million kilometres from Earth.

The galactic mirror. Photo Nasa

This extremely expensive project, launched from French Guiana, aims to deploy within a total of four months its mirror system, Optical Telescope Element. Its primary mirror, measuring six and a half metres in diameter, consists of 18 hexagonal pieces made of beryllium, a strong but lightweight material resistant to high temperatures. To enable it to collect light, these are coated with a very thin layer of gold.

Simulation of the mirror in space. Photo NASA

Simulation of the mirror in space. Photo NASA

To analyse the light that will be reflected by these gold panels, scientists will also have to ‘go through the mirror’, to give visible form, born of their imaginations, to the data provided so as to one day reach the ‘secret of secrets’.

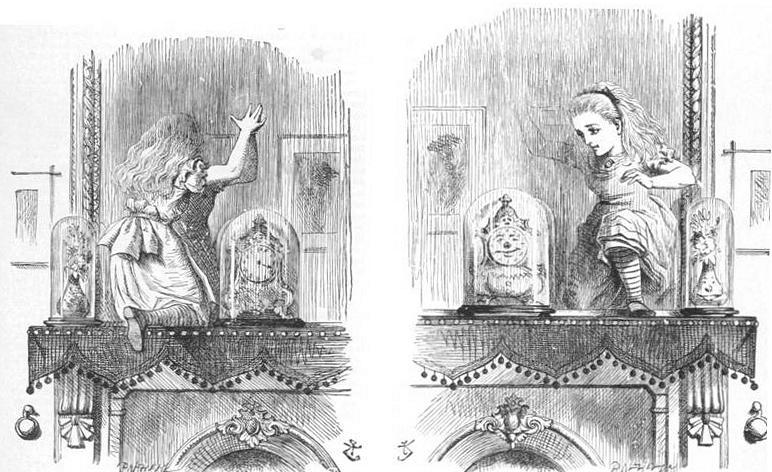

Mirrors contain a particular danger, which is also very much of our own day: the Narcissus effect. This occurs when an observer falls in love with their own image and is condemned to circle it.

Narcissus by Caravaggio (1594-96), Wikipedia

These are tremendous fixations that are very recurrent today: there are thousands of examples of people, countries, leaders, groups, societies trapped by an exalted image of themselves. When this happens, there is only one solution: that someone breaks the mirror in an instance, in order to be able to pass through to the other side and see what they have refused to see until then. But, alas, how communities take care of their mirror, the little mirror that tells them what they want to see and hear! Here, the mirror does not reflect reality: the image is already fixed on the false mirror’s surface, so that, like a stamp, it may be used to mark devout believers.

The metaphor of the mirror offers rich material, and in the theatre defines, for example, the whole genre of puppets, which plays constantly with reflections, either implicitly and unconsciously, or in full knowledge.

Image of ‘The Watching Machine’ by Macarena Recuerda Shepherd. Photo by Jesús Atienza

Image of ‘The Watching Machine’ by Macarena Recuerda Shepherd. Photo by Jesús Atienza

It is curious that in our homes we feel the need to place typical Christmas decorations around mirrors, as if we wished to wrap them in a halo of the magic of this time of year, with different meanings depending on geography and culture. Do we do it, perhaps, to be able to cross through them some sleepless night and look out the other side, without breaking our necks? Or to invite other beings —the Santa Clauses, the Three Wise Men, the elves and others— indicating that this mirror is also a door through which they can pass. We leave them offerings: candy, nougat, milk and, if they are lucky, some money in a saucer.

The elf Puck, a character from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The elf Puck, a character from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Painting by Joshua Reynolds, 1789. Wikipedia

The celebration of Christmas, and Epiphany on 6 January, are inventions with reflective attributes: parents, children, siblings, grandchildren try to get together at least once a year and take a family photograph. Depending on the image we see reflected, we either smile with pride or fix a half smile, with little desire for anything, anxious for the party to be over. Luck and gifts are not given in equal parts and, as tradition has it, the secret of happiness is to be content with what you have.

Incidentally, Titeresante is also a mirror, or tries to be: reflecting the diverse reality of what goes on in the sector of puppetry, objects and visual theatre. A polyhedral mirror, with multiple surfaces, that owes its existence to many hours of work.

To leave behind 2021 and enter 2022 is also to go through a mirror of sorts, that in which we have seen ourselves reflected during the whole of the year we leave behind. On the other side, newborn, 2022 opens its doors on to novel experiences and the unfamiliar. We do not know what awaits us, but let us hope the journey will be happy and fruitful!

From the looking glass of Titeresante, then, and its multiple surfaces, we wish all our friends and readers:

A Happy New Year 2022!!

Translated by Rebecca Simpson