The PuppetPlays International Conference on Literary Writing for Puppets and Marionettes in Western Europe (17th to 21st centuries) took place in Montpellier, France, from Thursday 14 to Saturday 16 October 2021. It was held at the Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, the institution responsible for organising the event. Given the length of the talks and our intention to provide the most complete account possible of the Conference, we have divided the article into three parts to facilitate reading. The second and third parts are to be published at later dates.

See Part II here and Part III here.

The PuppetPlays project

This is the first international conference run by PuppetPlays, a research programme on the repertoire of plays for puppets and marionettes in Western Europe from 1600 to the present day. It is led by Didier Plassard, Professor of Drama and Performance Studies and the author of important books on the Marionette. The Conference was organised by the Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3. The project is a recipient of the European Research Council (ERC) 2018 “Advanced Grant” and will be funded for 5 years (1 Octubre 2019 – 30 September 2024) by the European Union as part of Horizon 2020 (ERC-GA 835193). (see here)

The principal objectives are:

– to collect a representative corpus of works written for marionettes and puppets in Western Europe (specifically Germany, Austria, Belgium, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Switzerland) from the 17th to the 21st centuries. – to identify the characteristics of theatrical writing for marionettes and puppets according to periods, cultural influences, production conditions and audience types; – to demonstrate the contribution of these repertoires in the construction of a European cultural identity.

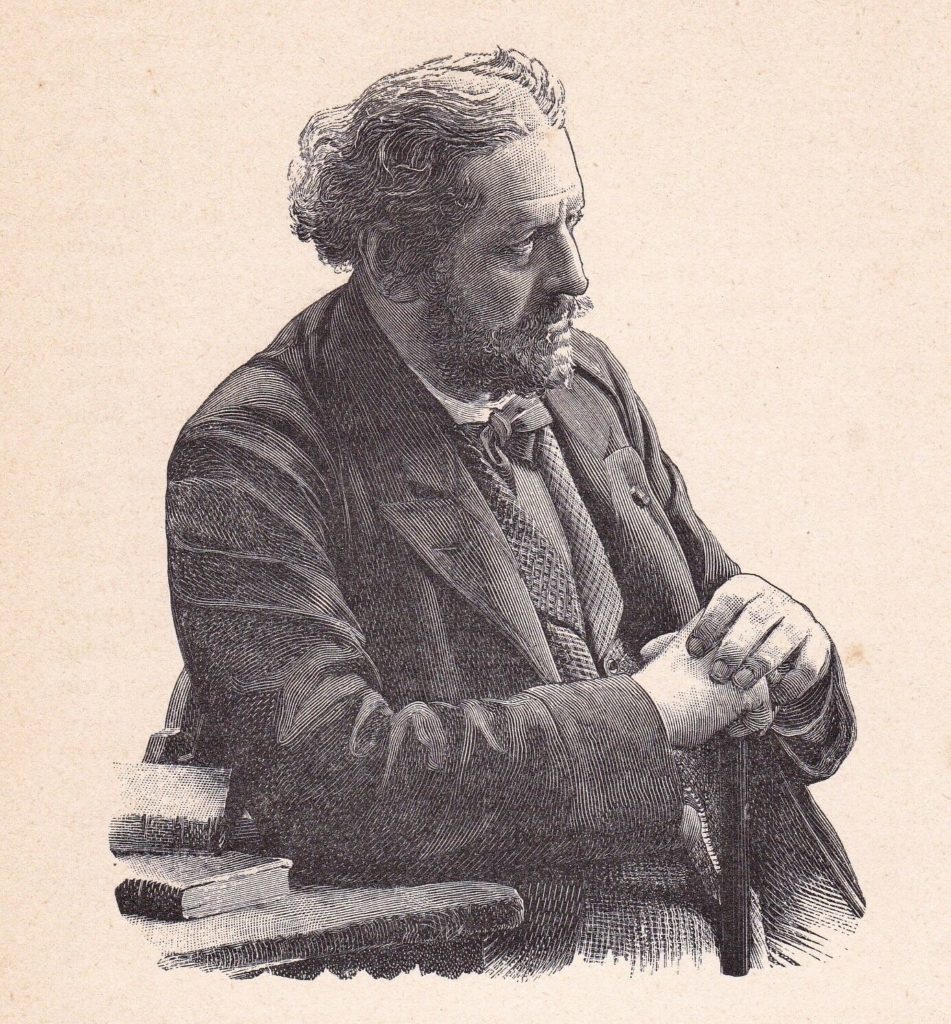

Didier Plassard in his opening talk at the Conference

Didier Plassard in his opening talk at the ConferenceThe team directed by Didier Plassard has been working in pursuit of these aims for the last two years. A strong point has been the creation of a digital platform whose database makes available to researchers, artists, teachers, students or others, an anthology of texts and a vast collection of documents. A written synthesis by Didier Plassard will be published at the end of the project and, in total, two international Conferences will be held (the first in October 2021, described here, and the second in 2023). The project is also committed to stimulating and accompanying young researchers interested in the subject, with grants for theses and a number of postdoctoral grants.

The Conference

Never has such an important meeting been held on literary texts for puppet theatre, featuring so many speakers and participants, and delivered for the most part from a rigorous academic stance.

Thirty speakers from various European countries were involved. Additional activities included a round table featuring four French authors who have written for the modern puppet theatre, a round table with four critics from different countries discussing their conclusions about the ideas that emerged during the Conference, three presentations offered by way of introduction to the three sessions (keynote speeches), and a workshop given by the company A Tarumba of Lisbon together with Paulo Duarte for students from the Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3.

All of this was complemented by meetings and round tables between the speakers, and two shows: a piece that was the outcome of the workshop-laboratory directed by A Tarumba, and the play Alors carcasse, with text by Mariette Navarro, directed by Bérangère Vantusso. Both could be seen at the Théâtre La Vignette. (see the Conference programme here)

‘Plays that escaped fire’

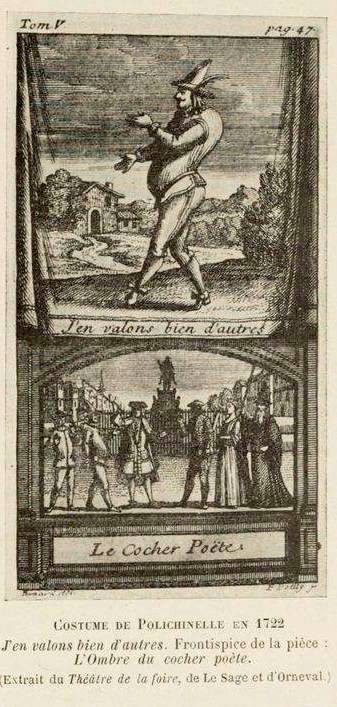

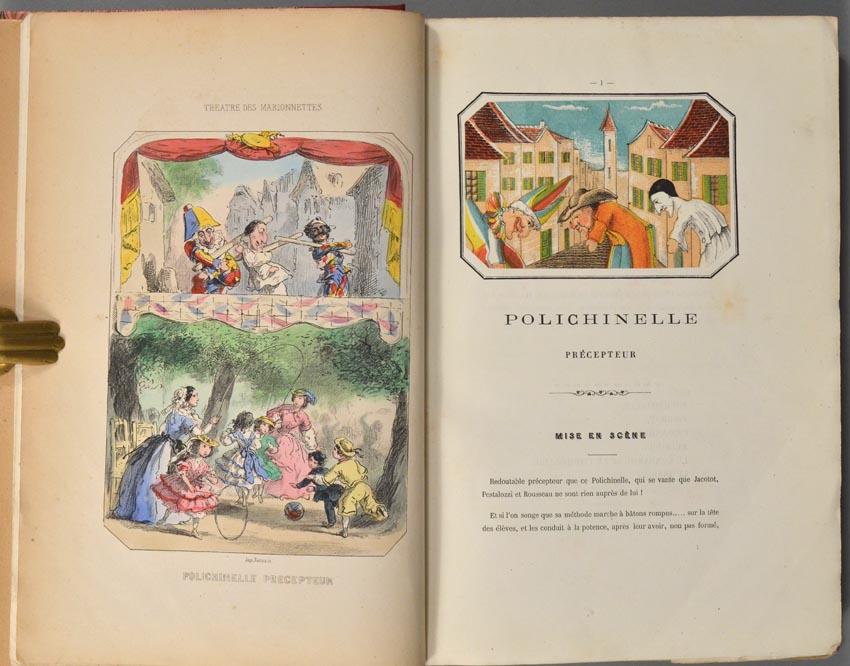

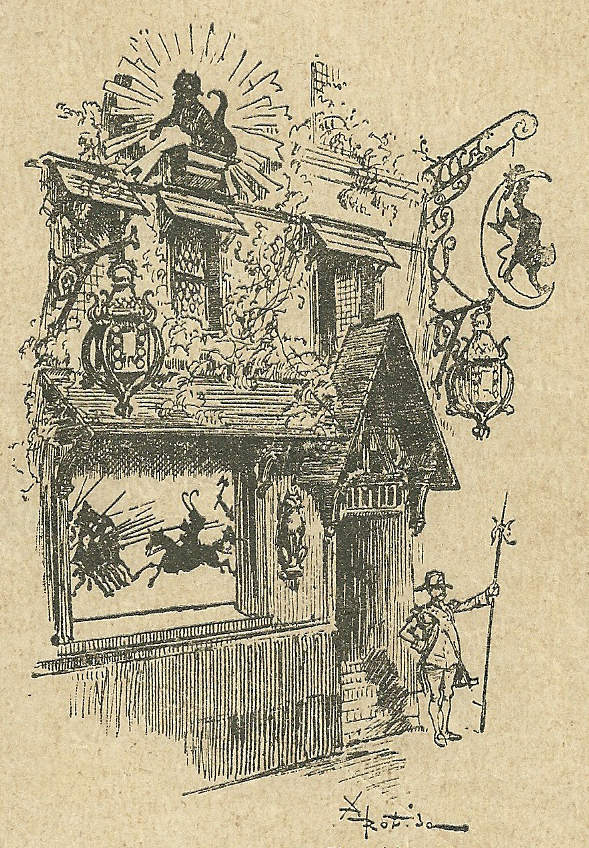

The overriding theme of the Conference was admirably established in the opening talk, or first Keynote speech, by Didier Plassard, the ideologue and creator of PuppetPlays. With the title ‘The Marionnette and the author: towards a reading of plays that escaped fire (echappées du feu)’, Didier’s point of departure is an anonymous collection published in 1717 (Pièces échappées du feu, Plaisance: 1717), containing several dozen texts in verse and prose. Of these, it is the first work that is placed under the spotlight: Polichinelle demandant une place dans l’Académie (Polichinelle Requesting a Seat in the Academy).

This short work is attributed to Nicolas de Malézieu (1650-1727), well-known in his day as a man of letters, Greek scholar and mathematician, himself a member of the French Academy. His text is the only one that has survived from the repertoire of the ‘Brioché’ family, who apparently performed the play for many years. Brioché was the name assumed by Pierre Datelin (b. unknown, d. 1671), father of Jean Datelin, who was famous in his time. Pierre Datelin, then, was the first in a line of puppeteers who for five generations went by the name of Brioché. He is considered as the first French puppeteer to perform Polichinelle, in a French language version of the character from the Neapolitan mask tradition. His venue was a puppet booth beside the Pont Neuf in Paris. The text allows us to deduce the form such a farce would have taken as performed at the Foire de Saint-Germain or by the Briochés, for whom Polichinelle was a principal character.

This work ‘that escaped fire’ serves Didier Plassard as a metaphor for the many puppet plays that managed to evade oblivion, and for that ‘general fire’ which has consumed a vast portion of the repertoire, now rendered forgotten and unseen. It is symptomatic, for example, that none of the pieces performed by the theatres of La Maquina Real in Golden Age Spain, and so few of those performed with marionettes in 17th and 18th century London, have been preserved.

As Didier explains, the Conference aims to revisit those works that have escaped fire, without the prejudices that typically lead to the undervaluing of this genre of dramatic literature; prejudices that can be ascribed not only to historians and academics, but also to puppeteers, who dismiss them as impossible to perform because of excessive wordiness or for being “too literary”.

Hunting for texts in the historical records of European puppetry

Many of the speakers at the conference have dedicated themselves to hunting for forgotten or unknown plays that were written either explicitly, partially or with dramatic allusion, for puppet theatres. For those interested in such matters, it is great news that so many speakers took part in the PuppetPlays Conference. The ‘trophies’ on display in Montpellier may be considered the tip of an iceberg, which will emerge little by little. Undoubtedly, initiatives such as this one devised by Didier Plassard are a much-needed stimulus to enable what has ‘escaped fire’ to be recognised, catalogued and studied by specialists; and perhaps to be performed by puppeteers. What we discover from these talks given over three days, stimulates the appetite for the task ahead and for where it might lead.

The presentations ranged freely through different time periods. Between the 17th and 21st centuries the road is long, traversed by numerous cultural currents of one tenor or another, from the most popular, jovial and sometimes vulgar – with the figures of the various European Pulcinellas as the principal drivers of jocose outbursts – to the most exquisite and refined poetic or philosophical visions of this great ‘bodily metaphor’ of the puppet, as some have called it. This canter through time eventually carries us to the historical avant-garde of the 20th century, and from there to our own day and the adventure of creative intersection and experimental hybridisation of stage languages.

So, let us review these contributions in chronological order, from the earliest period to the present day, with a view to offering a broad, and more or less organised overview of the papers given in Montpellier. We will attempt to synthesise the different talks, not in order to summarise them but to highlight their most significant points, so as to encourage readers to listen to, or read them in full since they are all of great interest.

We invite anyone who wishes to learn more about the many, varied lectures to visit the website. The majority are available as video recordings. (see here)

Polichinelle in the 18th Century

Didier Plassard’s introduction in which he spoke about Polichinelle Requesting a Seat in the Académie, was followed by a fascinating and entertaining talk by Françoise Rubellin. A Professor of Eighteenth-Century French Literature at the University of Nantes, her subject was the fairground marionette operas performed at the Foire Saint-Germain in Paris, during the 18th century. Very little is known about these operas, given – as Rubellin explains with great irony – existing prejudices.

First, she says: forget the idea of the small booths for glove puppets that come to mind so readily and are seen in so many contemporary engravings. In contrast, the theatres where these works for marionettes were performed were sumptuous: spacious for the performing artists and comfortable for the spectators. One of the surviving libretti details the need for six actors with vocal roles, eight puppeteers and six musicians; these were important companies using fairly complex staging.

Second: preconceived notions exist about the audience. Forget the idea of shows for popular audiences, the man and woman on the street. Rather, they catered to a rich variety of spectators, including the popular classes, of course, but also the intelligentsia and, invariably, members of the lesser and upper nobility. Allusion to contemporary texts, to works performed at the Comédie Française and fashionable plays in general is indicative of a theatre aimed at audiences who were complicit and in-the-know.

Third: ignorance of the history of the theatre of fairs, complains Françoise Rubellin. The monopoly on spoken theatre that had been granted to the Comédie Française, and the subsequent banning in 1722 of actors in comic opera, encouraged people to have recourse to marionettes. This led to the invention of opéra comique for marionettes, of which many texts have been preserved.

Fourth: the prejudice that important authors did not write for marionettes. This is false, if we look at the extraordinary repertoire of plays preserved, basically by three well-known authors: Denis-Joseph Carolet (1697-1739, of whom 31 titles are preserved), Adrien-Joseph de Valois d’Orville (1713-1780, author of many parodies of operas, ballets and tragedies for marionettes, produced between 1735 and 1740) and Louis Fuzelier (1674-1752, a highly respected author of the period, who wrote for every theatrical genre and, incidentally, was considered the inventor of the comic opera for marionettes in 1722).

As the speaker recommends, more can be learned about this question by reading Parodies d’opéra au siècle des Lumières. Évolution d’un genre comique, by Pauline Beacé. Presses Universitaire de Rennes, 2013.

Marionettes in 17th century London

From Paris we move to London, with an entertaining talk by Daniel Yabut, a Research Engineer for the CNRS, affiliated to the Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3. He proposed a broad vision of what defines a puppet, with a view to including in the PuppetPlays database, perhaps, not only plays written ‘for’ marionettes but also ‘with’ marionettes. In this sense, after indicating the scarcity of texts written ‘for’ puppets, he emphasised, in contrast, the wealth of stage elements and props that could be included as belonging to the world of animated or static stage figures, which are so closely related to marionettes.

In fact, as Daniel Yabut points out, there are only two works from this period that can be considered to have been written for puppets, both of them by Ben Jonson (1572-1637), the contemporary, eight years the junior, of Shakespeare. Bartholomew Fayre is the most important of these, the second play being A Tale of a Tub. In the latter, puppets appear in a play-within-the-play, also called A Tale of a Tub; experts agree that it was performed with shadow puppets: two-dimensional figures illuminated from above. In Bartholomew Fayre, the stage directions indicate that the character, Lantern Leatherhead, enters with the puppets in a basket, which suggests that they are not string marionettes. (It is interesting to note, in the dialogue, that these puppets are referred to as ‘actors’ and ‘small players’.)

For Daniel Yabut, the challenge is how to add material to a database about literary texts for marionettes when, supposedly, only two works exist. The speaker consulted the EEBO, Early English Books Online, and found about 1000 references to ‘puppet’ or ‘motion’, a term used for a puppet play; while some were of intrinsic interest, he found nothing relating to specific puppets or named puppet works, other than these two plays by Ben Jonson.

On the other hand, if we accept Scott Shershow’s definition of ‘puppet’ as any object manipulated on stage we can clearly extend the list of texts, since so many objects and artefacts are used in the theatre of this period.

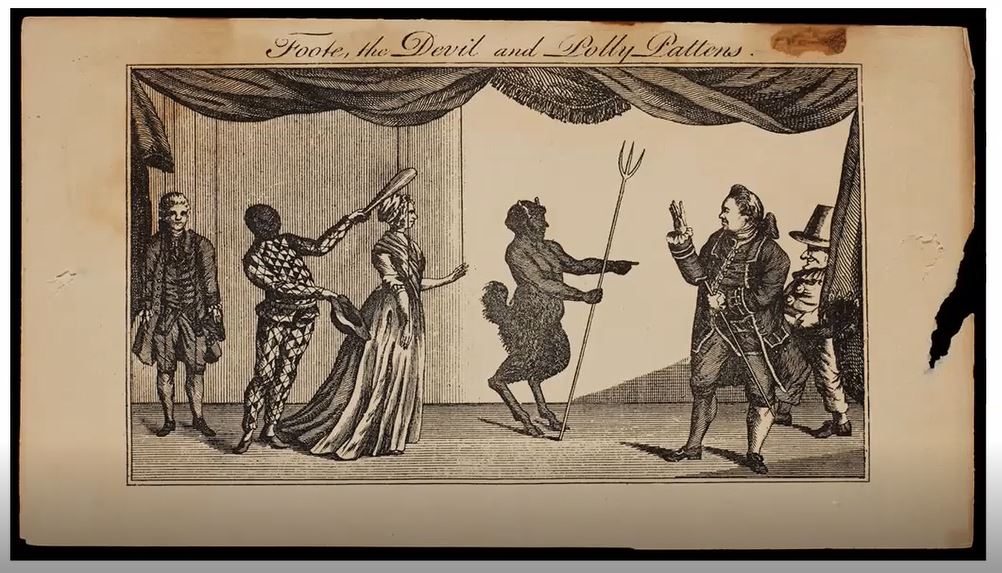

Henry Fielding and Samuel Foote

Remaining in London, though now in the following century, Marc Martínez, Professor of Eighteenth-Century British Literature at the University of Rouen, gave a talk on ‘Satire and theatricality in the puppet plays of Henry Fielding (1707-1754) and Samuel Foote (1720-1777)’. These two rival authors performed successively with puppet shows at the small ‘alternative’ theatre of Haymarket, in London’s West End, Fielding in 1730 and Foote from 1750. Henry Fielding had higher literary ambitions (later, after returning to the legal profession, he would make his name in fiction with the picaresque novel Tom Jones published in 1749, among others); he used puppets, sometimes played by actors, as a symbol of the degeneration of dramatic art, as a vehicle for satirical denunciation and as a meta-theatrical process. In the case of Samuel Foote, ‘he appropriated the articulated, elevated language of pathetic tragedy (also known as she-tragedy) and the sentimental novel, in order to parody and stigmatise the decadent codes of a sclerotic theatricality’.

A Treatise on the Passions, 1747. Illustration taken from the talk by Marc Martínez

A Treatise on the Passions, 1747. Illustration taken from the talk by Marc MartínezMarc Martínez began by explaining that puppets evinced a lively interest in 18th-century London audiences, with shows at summer fairs or in temporary theatres set up for the occasion, though never on the stages of theatres holding a Royal warrant. The puppet was considered an unworthy form of entertainment, in spite of the fact that it might appeal to both popular audiences and members of the English aristocracy.

We should not imagine that popular culture – where the puppet is generally to be found – is a locus of resistance or struggle against the dominant classes. Despite the subversive, carnivalesque elements it may generate, it is profoundly imbued by the cultural and social hierarchies within which it functions. This clarification allows us to observe with greater precision the exchanges and connections between the worlds of popular and erudite cultures.

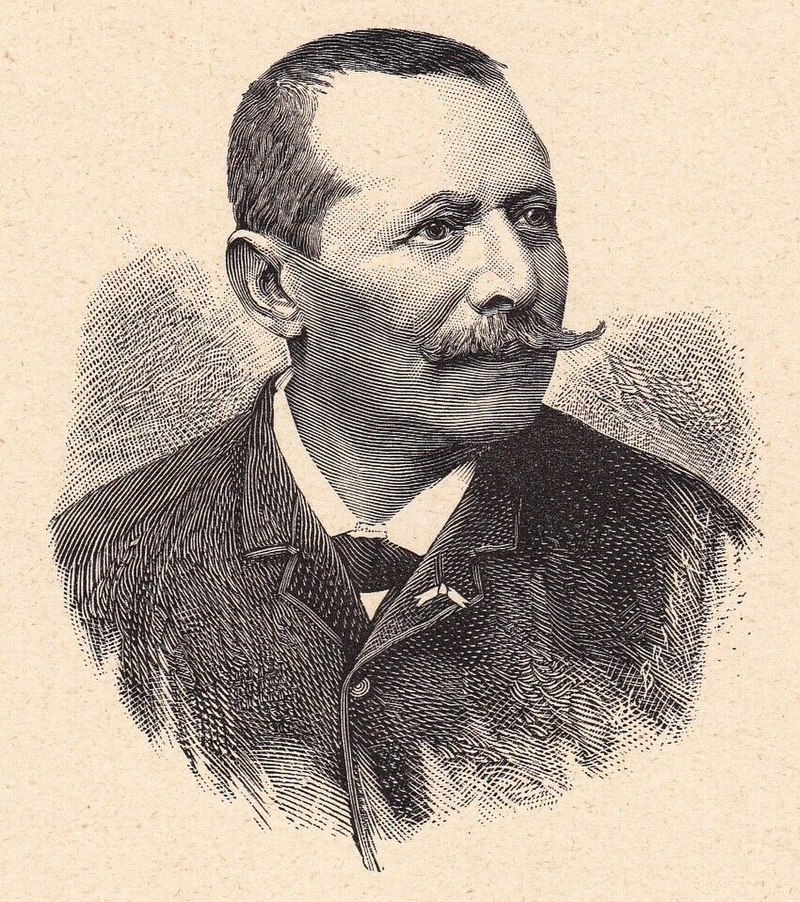

Henry Fielding, c. 1743, engraving by Jonathan Wild. Image, Wikipedia

Henry Fielding, c. 1743, engraving by Jonathan Wild. Image, Wikipedia

Fielding occupied the small, alternative Haymarket theatre after his comic plays had been rejected by the Theatre Royal Drury Lane; his works leaned towards satirical farce, poking fun simultaneously at contemporary theatre and politics. Some years later, Foote, a veritable filibuster of the stage, as Marc Martínez calls him, took over this same theatre. Both were driven by their desire for public recognition and their fascination with puppet theatre. And while Foote, an exceptionally gifted mimic, never renounced the regular creation of new comedies, displaying his genius in satirical reviews, for Fielding the puppet would be an occasional resource, which he scorned because it did not measure up to his literary aspirations.

‘For these authors, trapped halfway between lowbrow and highbrow culture, the puppet – alternately despised and exalted – functioned as a symbol of the degeneration of dramatic art, as a vehicle for satirical denunciation, and as a meta-theatrical process,’ says Marc Martínez. His aim is to ‘analyse how these authors adapt the dominant discourse to their satirical practices while maintaining the paradoxical nature of the puppet’.

‘In Fielding, the puppet serves as a satirical metaphor for the degeneration of the theatre, which, by analogy with this despised genre, is degraded to the level of a sideshow at the fairground. In Foote, by contrast, established genres are revealed as exhausted, and plays performed by actors to be merely mechanical, as illustrated in his piece The Primitive Puppet Show, later renamed Piety in Pattens, or the Handsome Housemaid.’

This talk by Marc Martínez clarifies the meaning of these plays by two authors who are, simultaneously, so close and so far apart.

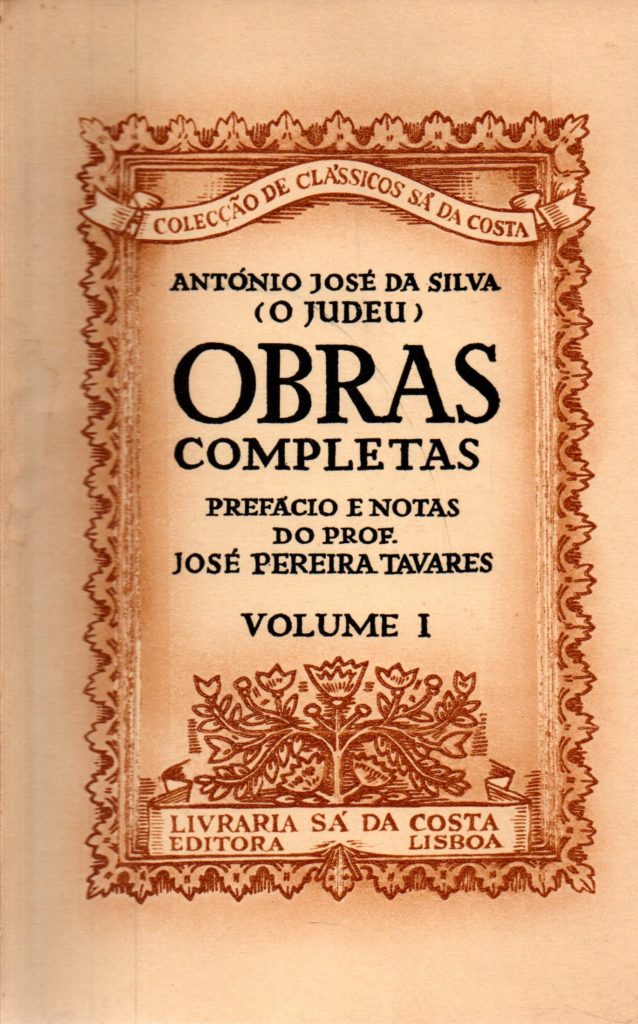

The sophisticated comic operas by António José Da Silva ‘O judeu’

Still in the same century, it was Carlos Gontijo Rosa, a post-doctorate researcher at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo in Brazil, that undertook to speak about António José da Silva ‘O Judeu’ (1705 Rio de Janeiro – 1739 Lisboa), considered Portugal’s greatest 18th-century playwright. From 1733 to 1738 he wrote what are known as ten jocose-serious works, tragicomedies in the Spanish mode but structured in arias and recitative in line with the Italian operas fashionable in his time. All were premiered at the Teatro del Barrio Alto, which was destroyed by the Lisbon earthquake of 1755.

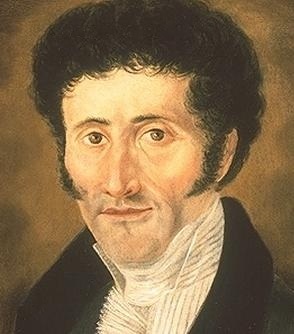

António José da Silva. Museum of the Inquisition, Mexico. Image, Wikipedia

António José da Silva. Museum of the Inquisition, Mexico. Image, WikipediaGontijo Rosa clearly explained this double Spanish and Italian influence on the works of ‘O Judeu’. According to the publicity of the time, they were written in response to Portuguese taste; and they made the most of the ambiguity offered by the figure of the ‘gracioso’ or comic, who maintained a direct contact with the audience.

António José da Silva’s work is, sadly, little known outside Portugal where his plays have been frequently staged. Of particular note are versions with marionettes (performed by the company São Lorenzo e o Diablo, for example): plays such as Vida do grande D.Quixote de la Mancha e do gordo Sancho Pança (1733) and Os Encantos de Medeia (1735).

Marionettes by the company São Lourenço e o Diabo, in the Museu da Marioneta de Lisboa, from their version of ‘D.Quixote de la Mancha e o gordo Sancho Pança’, by José António da Silva. Image, Museo da Marioneta

Marionettes by the company São Lourenço e o Diabo, in the Museu da Marioneta de Lisboa, from their version of ‘D.Quixote de la Mancha e o gordo Sancho Pança’, by José António da Silva. Image, Museo da MarionetaThe Inquisition ended the life of ‘O Judeu’ while still a young man, his ‘flesh relaxed’ (relaxado em carne) as the term was, which is to say, garroted and burnt at the stake, in an auto-da-fé in October 1739, for his condition as a Jew ‘convicted, denying his guilt, and relapsed’.

When were plays first written for marionette theatre in Germany?

Lars Rebehm, director of the Puppentheatersammlung in the Museum für sächsiche Volkskunst of Dresden, answered this question in the talk he gave on Saturday morning. The first time puppets are mentioned in a positive sense, he argues, was by Johann Gottfried Herder in 1769, although it would not be until 1770 that the first reference occurs to puppet or marionette plays as literary works. On the other hand, says Rebehm, Goethe’s geistig-moralische Puppenspiel (1774) and the work “Marionetten-Theater” by Johann Friedrich Schink (1778), apparently written for marionettes, were puppet plays only in name. Nor did the Romantic period create works specifically for puppets, despite an undeniable enthusiasm for them.

It was the innovative marionette player Johann Georg Geisselbrecht, who came from a long line of shoemakers, that tackled the need for a repertoire for his performances. Already working as a self-employed puppeteer in 1790, Geisselbrecht wished to familiarise himself and compete with the best companies of the time, such as the Schütz and Dreher companies, popular in Leipzig and Berlin. With a fine stage setup and an excellent sense of humour, he attempted to renew his repertoire using plays from the contemporary theatre, but with little success.

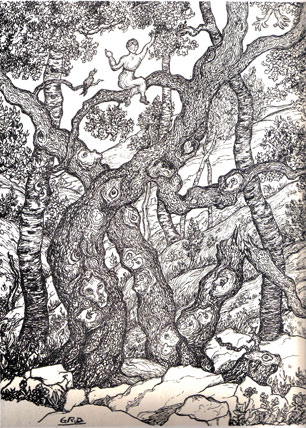

Illustration of Le fiabe di Carlo Gozzi, volume I, Bologna, Nicola Zanichelli, 1884. Image, Wikipedia

It was in the autumn of 1800 in Frankfurt that he met Clemens Brentano, still a student, who was enthusiastic about Geisselbrecht’s work and expressed a willingness to write for him, although in the end the idea did not prosper. Geisselbrecht sought desperately for a ‘Gozzi’ for his puppets, an author he adored (Carlo Gozzi, 1720-1806, wrote various works for the famous company of the comic actor Antonio Sacchi, 1708-1788).

The puppeteer attempted to work with other authors, such as Siegfried August Mahlmann in 1804, with moderate success. It was then that Johannes Daniel Falk, encouraged by his friend Goethe, offered him his play ‘Die Prinzessin mit dem Schweinerüssel’ (The Princess with the Pig Snout), which Geisselbrecht staged successfully; although an epilogue written by Falk in which he mocked actors in general led to certain problems. The arrival of the Napoleonic army in Thuringia (1806) put a stop to this very fruitful collaboration.

After collaborating successfully again on several occasions with Siegfried August Mahlmann, Geisselbrecht established working relationships, too, with the following authors: Julius von Voss (The Matron of Ephesus, and The Jew in the Barrel, in 1812), Karl Stein (Travestie of Doctor Faust, 1811, The Magnetdoctor, and Ulysses of Ithaca or The Triumphal Procession to Troy and the Return, in 1813) and Gerlach (Kaspar before the front, 1811).

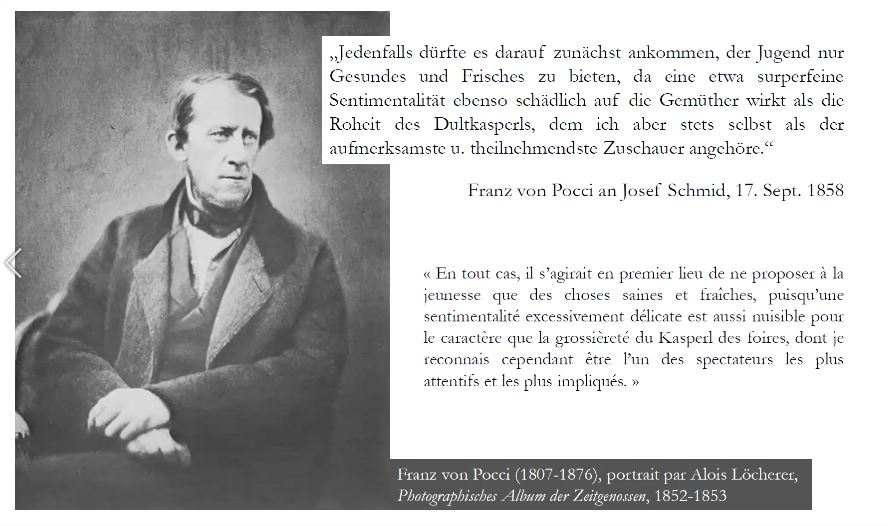

Geisselbrecht died in 1826, the same year as his friends and authors, Falk and Mahlmann, bringing to a close a very productive period for the puppet repertoire. It would not be until 1858, with the collaboration between Franz Graf von Pocci and Joseph Leonhard Schmid, ‘Papa Schmid’, in Munich, that a fresh repertoire of texts for the marionette theatre would again emerge, although the performing rights for Pocci’s plays only became available in 1906.

Franz von Pocci’s work: Barbarism and Childhood.

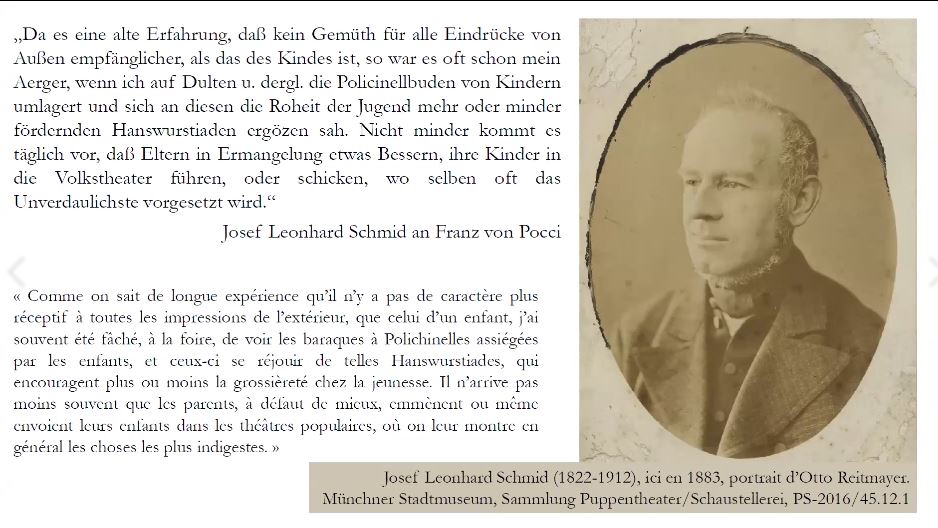

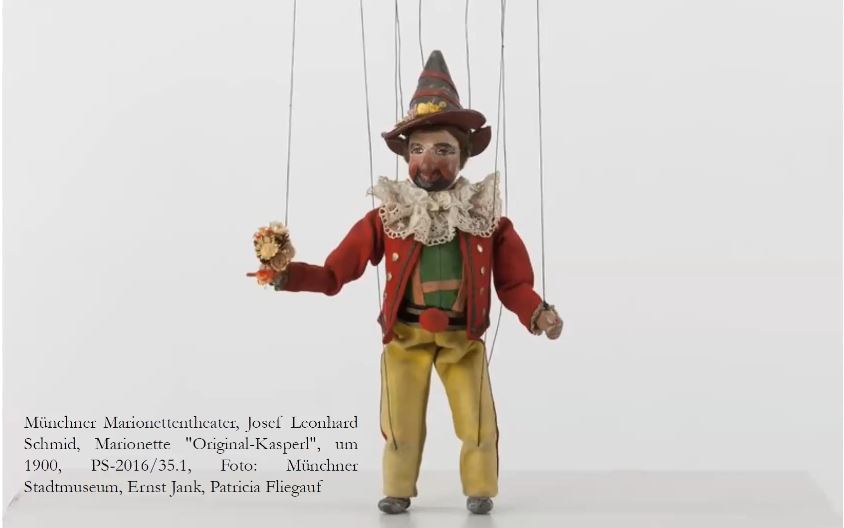

Given that we are in Germany, and having cited Pocci and Papa Schmid, it makes sense to turn our attention to the talk by Jean Boutan, postdoctorate fellow for the PuppetPlays project and a doctor in Slavic studies at the University of the Sorbonne in Paris. Jean Bouton’s subject was the corpus of (over a hundred) plays by author, composer and illustrator Franz von Pocci, for the marionette theatre for children. These he created at the petition of his friend, the puppeteer Josef Leonhard Schmid (1822-1912) better known as Papa Schmid, who wished to inaugurate a permanent marionette theatre in Munich. Created in 1900, this theatre continues to raise its curtain every day.

Illustration taken from the talk by Jean Boutan

Illustration taken from the talk by Jean BoutanWhat is interesting about this case is that Pocci, a German with an Italian father, responded in his own particular fashion to Papa Schmid’s request to create a distinct repertoire from what was regularly seen in puppet booths at fairs, where the characters of Polichinela and Hanswurt (a traditional German comic character) displayed only the most vulgar and ‘indigestible of things’, according to Schmid’s letter requesting Pocci’s services.

But Pocci, instead of rejecting the popular register, reaffirmed it, recuperating the character of Hanswurt and particularly Kasperl, whom he referred to as Larifari. In the development of his plots, he substitutes the more extreme vulgarity for burlesque, satire and a mixture of genres, arguments and motifs. He criticises and avoids the lamentable strain of sentimentalism that was predominant in shows for popular audiences during the 19th century, substituting it for what, following Goethe, he calls ‘barbarism’. For Pocci, this concept designates an eclectic theatre, capable of adapting and combining well-known shows with absolute freedom. It is a barbarism with its own particular poetics, in which satire substitutes explicit morality.

Three works by Pocci from 1860 were given as examples: Kasperl and the Magic Flute, Hansel and Gretel, and Kasperl and the Magic Violin.

Kasperl Larifari, a particular kind of comedy and character, belonging especially to Austria and Bavaria, which still imbibed inspiration from Italy’s commedia dell’arte and its traditional characters.

The Munich Marionette Theatre. Photo, T.R.

The Munich Marionette Theatre. Photo, T.R.The repertoire created by Pocci was so vast and impressive that it exerted its influence in German speaking countries throughout the 19th century and part of the 20th, and interested puppeteers from elsewhere, such as Duranty in Paris, according to Jean Boutan.

Four comedies by Giovanni Battista Zannoni

Now that we have crossed the threshold into the complex 19th century, a key period in the evolution of marionette theatre in Europe, let us consider the lecture by Francesca Cecconi, doctoral candidate in Philology, Literature and Performance Studies at the University of Verona, Italy, who spoke about four comic Scherzi published by the historian and anthropologist from Florence, Giovanni Battista Zannoni (1744-1832).

The talk focuses on the first four texts to be published in the vernacular Florentine language, in three successive editions (1819, 1825 and 1838). These were published anonymously although anyone with an understanding of the matter knew that the ‘regio antiquario’ of the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence was the erudite Giovanni Battista Zannoni.

This is unique: four plays for marionettes written in the Florentine dialect, of the highest quality, as is only to be expected from the pen of a writer who was not only exquisitely cultivated but also eloquent and very funny. The four works published, entitled Le gelosie della Crezia, L’amicizia rinnovata ossia la ragazzavana e civeta, La Crezia rincivilita per la creduta vincita di una quaderna, and Il retrovamento del figlio, are accompanied by the justification that the use of dialect is acceptable since they are mere works for marionettes; which is to say, small-scale honest entertainment. The same argument is applied to the disinhibited nature of the plays, full of jokes and witticisms. Francesca Cecconi explained how the characters relate and correspond to the characteristic commedia dell’arte masks, thus placing the four scherzi comici within the tradition of popular Italian theatre.

Image taken from the talk.

Image taken from the talk.The plays were performed in Le marionette di Casa Marchionni. But where was this house? Cecconi considers, as the most plausible hypothesis, that it was the home of a famous actress of the time, Carlotta Marchionni (1796-1864), whose father, Angelo Marchionni, was also a well-known actor, performing the characters Brighella and Arlechino.

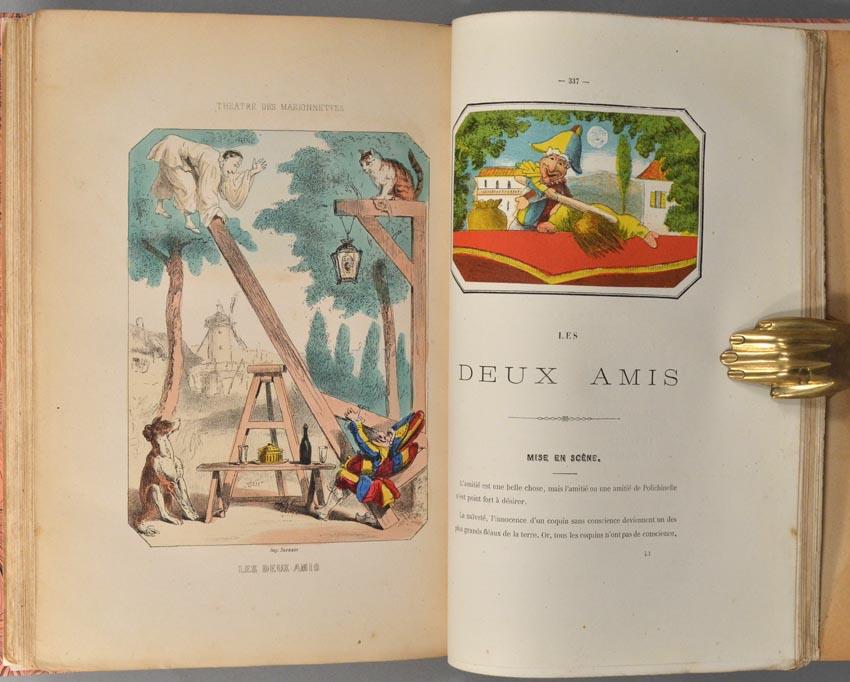

The glove-puppet repertoire of Louis Edmond Duranty

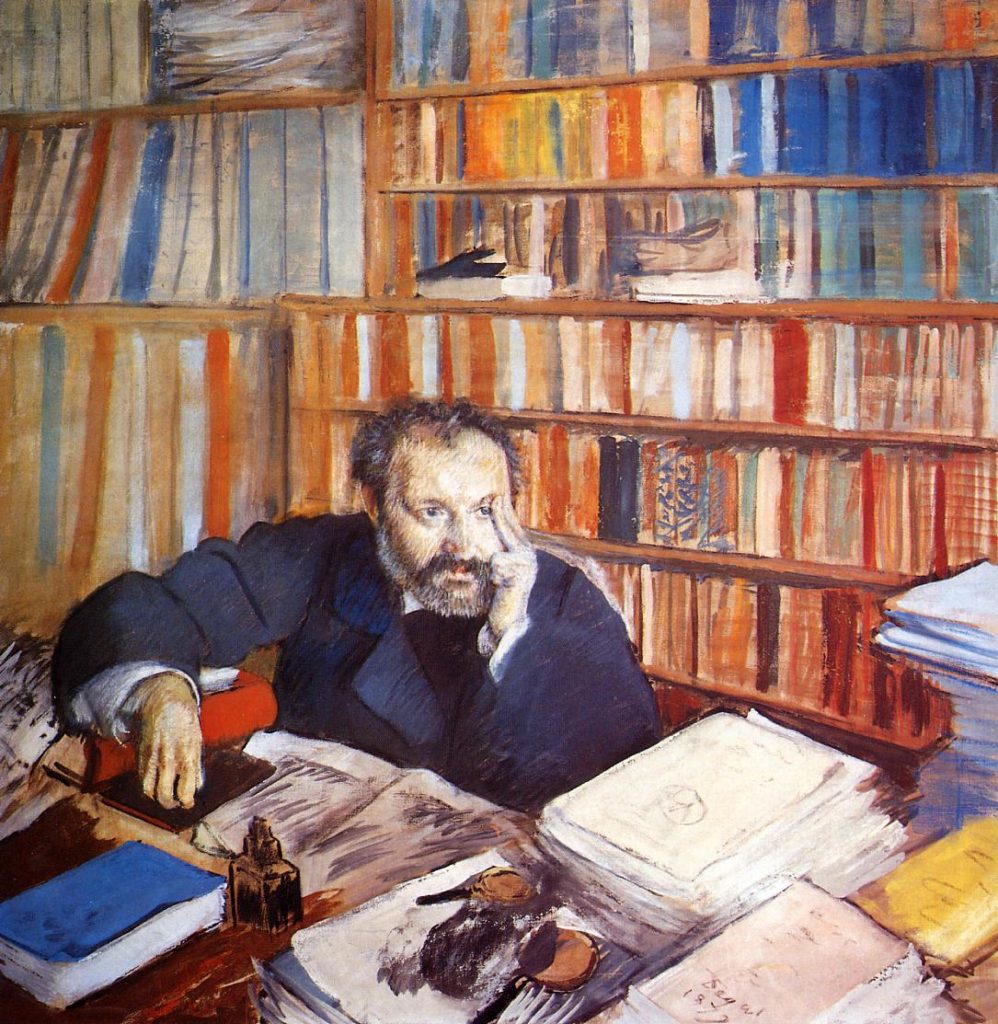

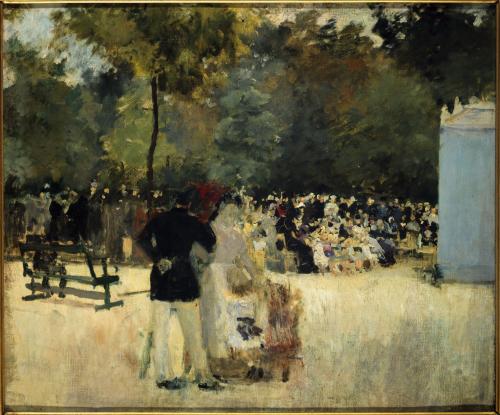

No visitor to 19th-century Europe can avoid making their way eventually to Paris, the world’s cultural capital at the time. Let us do so then, in the company of Carole Guidicelli, Doctor in Drama and Performance Studies at the Université Paris 3, and research engineer for the project PuppetPlays. Carole Guidicelli gave a talk on the repertoire for glove puppets of the highly regarded puppeteer, Louis Edmond Duranty (1833-1880), who, in 1861, established the Marionette Theatre of the Tuileries Gardens.

This author had already made a name for himself as a novelist and as a critic with an acid pen, who rubbed shoulders with the painters Degas, Courbet and Daumier, among others, and writers such as Baudelaire, Gautier, Dumas the younger, and Champfleury. From the beginning, his theatrical aim was clear: to procure a high-quality literary repertoire for glove puppets, with the help of some of the great writers whom he counted among his friends. However, the reality is that Duranty only managed to obtain a prologue in verse from the poet Fernand Desnoyers, with which he opened the theatre on 19 May 1861, he himself providing a short farce for the second half of the programme.

How interesting that Duranty should adopt Polichinelle as his alter ego, putting into the character’s mouth his opinion about what marionettes ought to be: a form of theatre that rebelled against the artificial sweetness and tedious morality drummed into young people by bourgeois society. This can be seen in Duranty’s play, Polichinelle précepteur (Polichinelle the teacher), whom he claimed was a better pedagogue than Rousseau, Jacotot and Pestalozzi. His student, Pierrot, after an intense course of Polichinelle’s form of education, ends up hanging himself. Our hero never thinks twice about applying his therapy with the slapstick, whether teaching or reprimanding and whenever necessary, which happens to be very often.

Polichinelle’s antagonist is Pierrot converted into a negative character, always envious of his opponents and therefore deserving of blows and punches.

Such content created rhythm and established the use of agile dialogue and stage action, the rapid linking of scenes and comic repetition. All in all, Duranty created a style for puppet theatre which has become a sort of canon for later puppeteers who recognised him as a master of glove puppetry to be followed or, at the very least, taken into account. We can mention masters such as Gaston Baty, Alain Recoing, Pierre Blaise, Emilie Valantin and Alban Thierry, all cited by Carole Guidicelli.

Lemercier de Neuville: marionettes and the bohemian literary scene

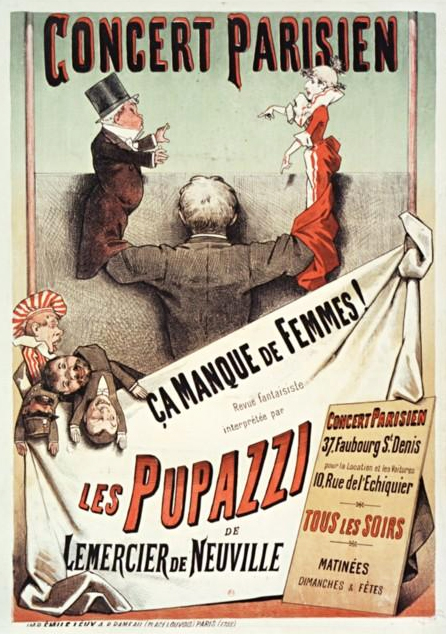

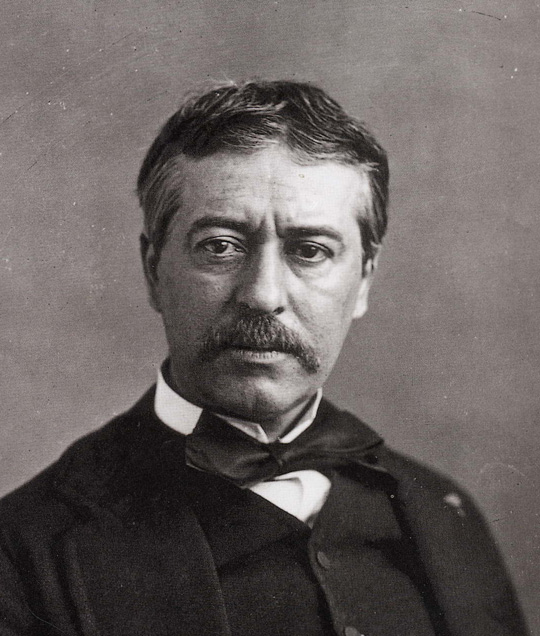

We find ourselves in the exuberant Paris of the 19th century as we listen to the words of the Director of the Department of Stage Arts at the National Library of France, Joël Huthwohl. A palaeographic archivist and theatre historian, he gave a paper on that fascinating character of bohemian Paris from the second half of the 19th century, Louis Lemercier de Neuville (1830-1918). Huthwohl’s work is based on the important Lemercier de Neuville collection, recently acquired by the National Library.

The journalist and playwright Lemercier created in 1860 Les Pupazzi, a satirical show for marionettes that was enormously popular during the Second Empire and the Third Republic. However, the most significant and surprising aspect of his enterprise was that he categorically refused to include the characters of Guignol or Polichinelle in any of his pieces. He avoided all traditional forms, including the use of the slapstick, or the blows of a club or truncheon, and declared himself the company’s sole author, a role he scrupulously fulfilled: he wrote more than 100 plays for marionettes –without counting divertimenti, monologues or conferences– the majority of which have been published.

The distance he kept from tradition led him to reject or, rather, show a total lack of interest in the world of marionettes when, in 1882, two years after he had abandoned his theatrical adventure with the Pupazzi, he published a book entitled Histoire anécdotique des marionnettes modernes, and later a work about shadow puppets that he called Les Pupazzi noirs in 1897.

Joël Huthwohl spoke about Lemercier’s life and his involvement in the fascinating literary and bohemian world of Paris. Self taught, and obsessed with the idea of making a name for himself in the literary world, Lemercier tried everything until he discovered, with the Pupazzi, a way to successfully attract audiences by converting the celebrities of his time into characters for his puppet booth, initially with silhouettes and cut-out images that he would stick on boards, adding the mechanisms himself, and which he manipulated. The texts are satirical poems, often in verse, that make fun of famous personalities and current events in Paris.

It was his friend, the painter Gustave Doré who would warn him of the limitations of his two dimensional figures, which could end up being tedious to audiences. Why not convert them into real puppets? From that point on, Lemercier made his own glove puppets, though he never abandoned his silhouettes, and began to write for the characters he created. Instead of the usual traditional heroes, he invented Monsieur Prudhomme, a caricature of a typical member of the bourgeoisie, who, in a certain way, brought Lemercier’s theatre closer to the traditional puppets of Guignol and Polichinelle. Lemercier did everything; he made the puppets, the backdrops and the silhouettes; he manipulated and spoke, and he wrote the music.

Joël Huthwohl also highlights the influence that revue shows had on the theatre of Lemercier; he was very familiar with revues, especially in their use of topical material, a characteristic of the Pupazzi theatre. It also, of course, made his works decidedly short-lived. This type of theatre was a forerunner of the Parisian cabaret of the end of the 19th century, such as the Chat Noir, founded in 1881, although, as the speaker indicates, Lemercier’s theatre is basically conservative and the liberties he takes never cross the line into provocation.

The unusual nature of Lemercier’s case, so different from the traditions of regular puppet theatre yet capable of importing into these languages the world of the revue and occasional short comedies, leads Joël Huthwohl to doubt whether it is appropriate to include Lemercier in the historical section of puppet theatre. However, he appears to reject such hesitation on considering the significance of Lemercier’s contributions and the uniqueness of his undertaking, so rooted in the world of puppetry.

The puppets of Maurice Sand

We will stay in France with Marine Wisniewski, Assistant Professor in French Literature at the Université Lyon 2, currently involved in editing the theatre of George Sand.

Leaving Paris for Nohant, near the city of Châteauroux, some 230 km south of the capital in the county of Indres, we find the large family house of the famous writer, George Sand, pseudonym of Aurora Dupin (1804–1876). It was the residence, too, of her son, Maurice Sand (1823-1889).

House of George and Maurice Sand in Nohant

House of George and Maurice Sand in NohantMarine Wisniewski spoke about the two private theatres that coexisted in Nohant: on the one hand, an actors theatre that George Sand, Maurice and their friends organised to entertain themselves during the winter months and, on the other, Maurice’s puppet theatre, set up initially by his creative mother and her friend, Eugène Lambert. Le grand théâtre et le petit théâtre, as George Sand used to call them, functioned side-by-side from 1847.

This was theatre, both in the small and large format, based on improvisation, along two different lines: while always open to improvisation, George Sand liked to write and fix her dialogues, whereas Maurice was fascinated by the ever-changing inventiveness of the characters of the commedia dell’arte. Together with Eugène Lambert, they created comic couples – Scapin and Fracasse, Scaramouche and Fracasse, Pierrot and Cassandre – with shows entitled Pierrot précepteur, Cassandre persuadé and Scaramouche brigand. The characters are Pierrot, Harlequin, Cassandra, Fracasse, Colombine, Scaramouche, etc. This fascination led to the publication of Maurice’s well-known book Masques et Bouffons in 1860.

According to Maurice, the similarities and differences between the two theatres served to define the contrasting language of puppets in relation to text-based and actors theatre.

Dolls, automata and wax figures

Without entirely abandoning Nohant, we remain in the 19th century as it draws to its close to hear the talk by Manuela Mohr, ‘Dolls, automata and wax figures: writing by and for puppets in the Hoffman inspired work of Maurice Sand, Jules Barbier and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes’. How do works of fantastic literature relate to the dramatic experience? This is the question posed by Manuela Mohr, who holds a doctorate in French Literature from the University Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, and is a post-doctoral fellow for the PuppetPlays project.

Portrait of Maurice Sand by Joséphine Raoul-Rochette–Calamatta (1817-1893)

Portrait of Maurice Sand by Joséphine Raoul-Rochette–Calamatta (1817-1893)

Mohr touches upon a subject that is fundamental for puppetry, the Double, a topic that was treated and developed by the Romantic movement in numerous works. The author E.T.A. Hoffman notably delved into the mystery and poetry of this intriguing figure of self-exploration.

Manuela Mohr sets out before us three works that are classics, though little-known by either the general public or puppeteers, myself included: Jouets et mystères by Maurice Sand, Arc-en-ciel by Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Les contes fantastiques d’Hoffmann by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, (Les Contes d’Hoffmann – an adaptation by Jules Barbier of their play – is, of course, famous as the libretto for Offenbach’s opera).

In her analysis of the three works, Manuela Mohr focuses on the relation between human characters and animated figures: dolls, mannequins and automata. These are, rather, inanimate, acquiring life when touched by the human gaze. Mohr distinguishes between Sand’s work, in which ‘toys, dolls and living people coexist, get mixed up or metamorphose without this being viewed as problematic’, and that of Ribemont-Dessaignes and Barbier where ‘this same coexistence represents the haze of a disagreeable frontier between human and automaton, marionette and marionettised-actor’.

Mohr makes a very interesting observation, in a comment that appears in the written text of her talk, about the importance of optical elements (and the gaze in its broadest sense) and of reflecting surfaces present in the three works. Mohr says: ‘Artificiality is linked to themes, motifs and writing procedures. The texts contain indices that speak of an intimate drama told by means of the peculiarities of the marionette or the marionettised-actor. One of these indices is the optical dimension. The Sandman and Arc-en-ciel take their departure from a similar situation: two houses standing opposite each other, which leads to the observation of the animated female figure. The placing of the houses and the exchanges between their inhabitants evoke reflection and mirror-imaging. In the work of Ribemont-Dessaignes, vertical reflection is correlated with horizontal reflection.’ Equally notable is the presence of glass display cases containing the inanimate characters, serving as invisible and subtly mirroring barriers. Similarly, Hoffman’s spectacles: ‘Thus, the optical instrument with its purely textual presence, has an immediate influence on how the artificial creature is perceived.’

Mohr says: ‘Through its choice of a particular relationship with word and movement, dramatic writing for puppets deals with the human experience through the limitations of the puppet. And later: ‘Through the marionette, links are revealed between the animate and inanimate, between life and death. Writing for the marionette finds ways to express – in the form of words, images and rhythms – different modes of existence’.

Manuela Mohr’s talk should be of enormous interest to those who delight in relating the themes of the double and mirror-imaging to puppetry; it deserves to be followed with attention and care, given how packed it is with ideas and information.

We take this opportunity to remind readers that most of the talks are available on video (see here)

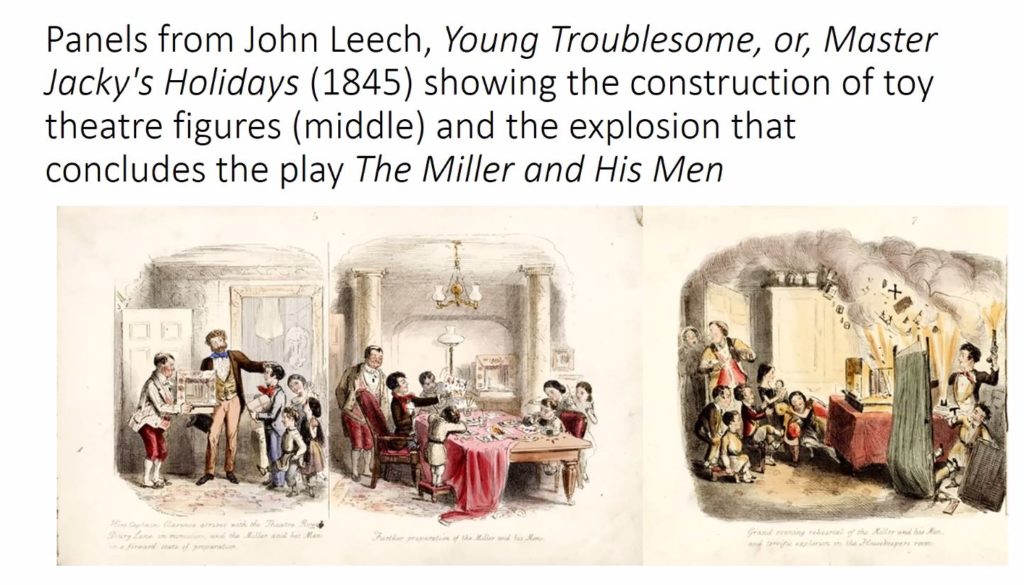

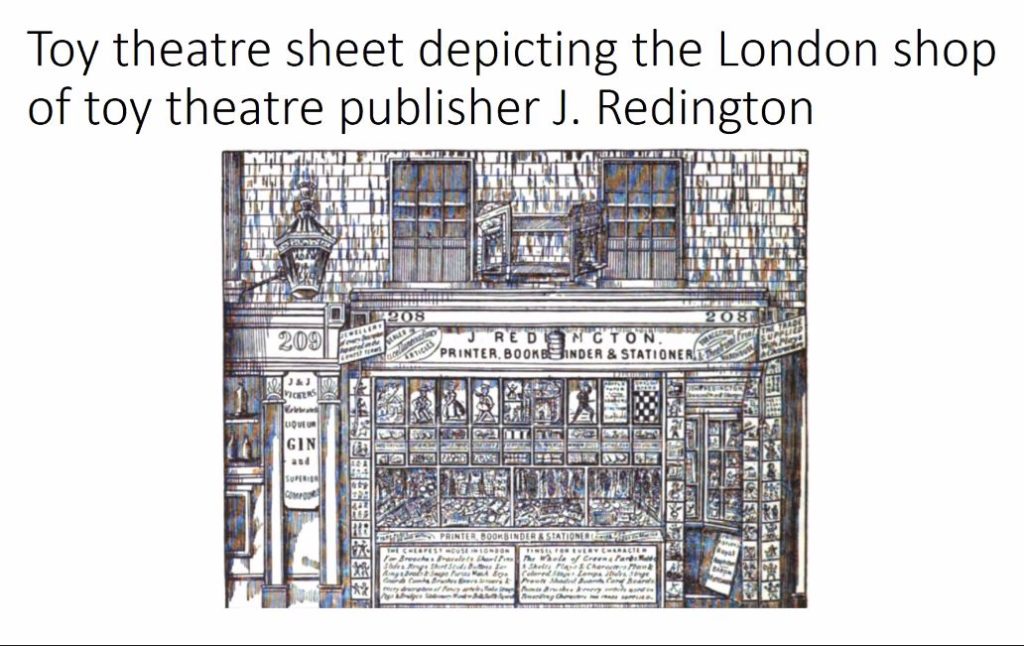

Toy theatres in London, between 1884 and 1962

Matthew Isaac Cohen, professor in Marionette Arts and Theatre Studies at the University of Connecticut, spoke about the fascinating and little-known subject of toy theatres, which is, at one and the same time, so poorly understood in terms of its history, the complexity of its history, and the repertoire that exists for this form of theatre. Focusing on the United Kingdom in the period between 1884 and 1962, Isaac Cohen ran through the principal authors who wrote for the toy theatre, as these small paper and cardboard theatres are known there. It is surprising to see so many well-known authors showing an interest in the genre!

Image, taken from the talk by professor Matthew Isaac Cohen

Image, taken from the talk by professor Matthew Isaac CohenTo begin with, this theatre was designed for the drawing-room, for the entertainment of children and adolescents who would perform these miniature works at home, with paper figures they cut out from sheets of card bought from specialised shops, together with texts, characters and sets. According to Matthew Isaac Cohen, this theatre, whose repertoire was intimately related to theatrical successes on the London stage, can be considered an early medium of mass communication.

This form of theatre was made available by numerous publishers, such as J. Redington and, perhaps better known, Benjamin Pollock’s Toy Shop, attracting writers such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Pamela Colam Smith, Jack B. Yeats, John Masefield, G. K. Chesterton, Reginald Reynolds, or the historian, collector of marionettes and puppeteer himself, George Speaight, who is known to have performed with historical toy theatres and others of his own creation. Mention was also made of puppeteers from the 1970s and 80s, such as Alain Lecucq and Robert Poulter.

Cabaret shows with puppets in the Paris of 1880-1900

We return to Paris to listen to Yanna Kor, Doctor in Drama and Performance Studies from the Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, and researcher into travelling puppet theatres in France in the 19th and 20th centuries; her doctoral thesis was on the theatre of Alfred Jarry. The talk by Yanna Kor concerns puppet and cabaret shadow shows from between the years 1880 and 1900.

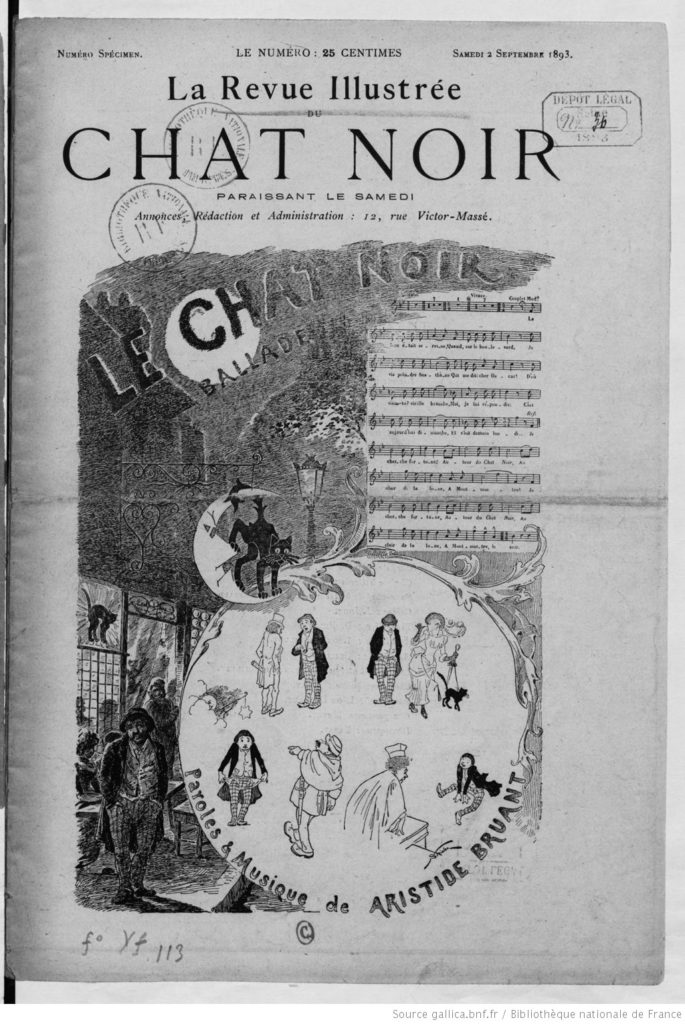

Revue theatre with puppets or shadow puppets was invented by Lemercier de Neuville, about whom Joël Huthwohl spoke extensively, and was an art form practised by authors such as Gyp, Maurice Donnay, Franc-Nobain and Alfred Jarry. Yanna Kor focused particularly on the work of Maurice Donnay (1859-1945), an emblematic author of the most famous Parisian cabaret of the time, the Chat Noir, founded in 1881 by Rodolphe Salis.

The speaker took her departure from a text by Robert Dreyfus, who, in an article about end-of-the-year cabaret shows, considered hundreds of shows in this genre and singled out the revue Ailleurs by Maurice Donnay, presented in the shadow show of the Chat Noir in 1892, as the ‘only one in which poetic fantasy, which should be the goddess and muse of this genre, was apparent.’

In order to clarify the relationship of the puppet with the genre of the topical revue, Yanna Kor analyses some of the shows performed with puppets or shadow puppets at the end of the 19th century, outlining and contextualising them in terms of two related practices: literary writing for puppets and the end-of-the-year revue.

Translated from the Spanish by Rebecca Simpson