Very soon, in the merry month of May, one of the events that puppeteers all around the world are most looking forward to will take place: Mr. Punch’s 350th anniversary. Preparations for a party are underway, and the celebrations will, furthermore, host the highest concentration of Professors ever known.

Although there are other characters equally long-lived as our London friend, few have survived with such tenacity and incredible energy as Punch, who has ever more adepts not only in England and the UK, but also in the United States, Australia, South Africa, and even Holland, (Neville Tranter recently created a show called “Punch in Afghanistan”). The reason for this energy is worthy of study, and Puppetring intends to pursue the matter with much attention. And we hereby announce that we will be following the anniversary festivities – an event not to be missed.

I was in London not long ago and given my enthusiasm for Punch I made the obligatory visits, paying my respects before the plaque opposite Covent Garden on which one can read that Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), the famous and marvellous diarist of the period, left a written record of the fact that in 1662 he saw a performance of Punch, given by the Italian puppeteer Pietro Gimonde.

Weary with walking through the city and visiting emblematic sites I returned to my hotel, not far from Victoria Station, where one of the owners asked me what I did for a living.

– I’m a puppeteer, I replied.

-What?, he said, hardly understanding. But I insisted. I thought that didn’t exist any longer. You mean people still go and see those things?

When I told him of my interest in Punch, he said, as one who drags up dark memories from the past:

– Oh, yes, me Mam and Dad used to put us in front of the Punch and Judy shows at the seaside, at Brighton. All the free stuff.

A disturbing reply for one such as myself who persists in dreaming of, or rather imagining, colourful remnants of London life in the midst of the dark city’s fog as portrayed by Dickens with such art. But it was this same Bed-and-Breakfast hotelier who, on learning that I worked in the theatre, heartily recommended the show that was on at the New London Theatre: War Horse.

– That’s a real puppet show!!!

Everyone had been recommending War Horse, which was sold out for months to come, in spite of having been running for two years already. But with this comment my mind was made up and I went to queue at the New London Theatre in the hope of buying return tickets. I was in luck, and got good tickets at a fairly high price. But it was worth it.

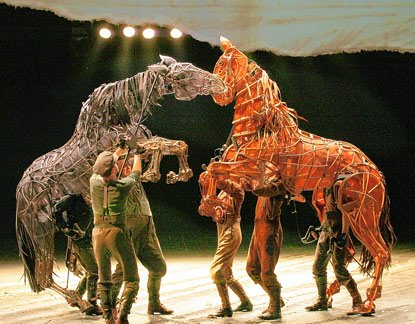

War Horse (a National Theatre production in collaboration with the Handspring Puppet Company) is based on the novel by award winning children’s writer Michael Morpurgo. It is directed by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris, with music by Adrian Sutton, which includes numbers sung by the company. The protagonist is a horse, first seen as a young colt manipulated – Bunraku-style – by three puppeteers dressed as stable lads. It then becomes a full-grown horse, a life-size puppet manipulated again by three handlers, but with two of them inside the horse (denominated in the programme “hind” and, significantly, “heart”), while the third “leads” it and manipulates the head. Later, a second horse, too, plays an important role and at a certain point the two animals spar and clash. The realism and quality of movement are extraordinary.

The actors – thirty or more, counting central characters, non-speaking roles and puppeteers -, are all in some way secondary characters in comparison to the protagonism and dignity of the horses that occupy the stage. And this is precisely the point of the work: to compare the animals’ dignity with the dehumanisation created by war. Dignity which is, in fact, merely our own, which we humans project onto these free and noble animals, and who are capable of uniting the feelings of men apparently opposed to each other through war. The moving portrayal showed how the horse managed to humanise civilians and military in extreme situations, giving them back the dignity that the barbarity of war had wrenched from them.

The triumph of puppetry on the London stage is this, – far removed from my dear Punch and other typical forms of the genre. War Horse is a show for everyone, undoubtedly visited by school groups and families, but fascinating and delighting audiences young and old, learned and popular.

So does this mean it’s all over for the old school, solo puppeteers? Not at all, and here to demonstrate the vitality of Punch in our day is his upcoming anniversary, the celebration of which will resonate, undoubtedly, far and wide. However, it is an indication of changing times and that the puppet theatre, far from disappearing as some were determined to think, has invisibly installed itself at the centre of contemporary stage thinking. So, back to War Horse, it would obviously be impossible to achieve such results with real horses, or at least so effectively.

The beauty of puppet theatre is the huge variety of possible forms it offers and permits. On one hand there is the well earned success of this fine production, War Horse, or the distinctive stagings of groups like the Fura dels Baus, (see Puppetring’s article on Le Grand Macabre), whose theatre continues to develop in visual and sculptural terms. And, on the other, there are the solo puppeteers, whether of Punch or other styles and tendencies; they seek the simplicity and synthesis of the minimal and are combative, offering useful answers, – powerfully and emotionally charged -, in the face of the increasing complexity of today’s world.

We offer these reflections as mouths water and engines rev, in anticipation of the coming Punch and Judy extravaganza, on Punch’s 350th Anniversary.

Translated and adapted by Rebecca Simpson

Sadly i am not in london to celebrate punches birthday but it looks marvellous. Have a great trip in Cuba, i

I enjoy your web sight very much.

Love Miranda